Section 2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Introduction

This is the second edition of the Labour Rights Index. The first edition was launched in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and covered 115 countries. The second edition is being launched at a moment when Pakistan, where the core team is located, is hit hard by the most devastating floods in its history, affecting 33 million people and claiming more than 1600 lives.

The second edition of the Index has 135 countries and covers labour market regulation affecting approx. 95% of the global labour force (3.57 billion workers). Labour Rights Index is a wide-ranging assessment of labour market regulations in 135 countries. It focuses on de jure (according to law) aspects of the labour market. The report scores 135 economies on 10 areas of labour market regulation. These are referred to as indicators. There is no other comparable project in terms of scope. The Index sheds light on a range of differences in laws/regulations on 46 topics or components across 135 countries.

The Labour Rights Index, while one of the many[1] de jure indices, is arguably the most comprehensive one yet in the field of workers’ rights, as it encompasses every aspect of the working lifespan of a worker and identifies the presence of labour rights, or lack thereof, in national legal systems worldwide. The Index measures decent work and provides detailed information on rights at work as well as the local legal framework for regulating the labour market.[2]

While grounded in SDG 8[3], the Labour Rights Index is a tool essentially directed at governments and international organisations. And even though the underlying document for this Index, i.e., the Decent Work Check, is aimed mainly at workers and trade unions, the Index targets national-level organisations like government agencies, trade union federations and multilateral organisations such as the United Nations. This Index measures all labour rights protections that have been referred to in Target 8.8.[4] The Labour Rights Index emphasises the importance of a well- functioning legal and regulatory system in creating enabling conditions for the achievement of Decent Work. As a corollary, it lays bare the adverse impact of lack of regulation or inadequate regulation on the smooth functioning of (a) labour market(s).

The 2010 World Social Security Report notes that even the widest and most expansive legal foundations cannot achieve the desired outcomes if these are not enforced and backed by sufficient resources. Nevertheless, strong legal foundations are a precondition for securing higher provisions and resources. There is not a single situation where a country provides generous benefits without a comprehensive legal basis.[5]

Similar points have been raised by Botero et al.[6] that formal rules, although different from “on the ground” situations, still matter a lot. Botero’s work forms the basis of the Doing Business Indicators by the World Bank. Research indicates that in the absence of legislation, even the wealthiest country in the world, i.e., the United States of America, is unable to ensure decent working conditions for a majority of its citizens. As explained by Heymann and Earle [7], “laws indicate a state’s commitment to its people, lead to change by shaping public attitudes, encourage government follow-up through inspection and implementation of the law and allow court action for enforcement.”

As an international qualification standard, the primary focus of the Labour Rights Index on larger administrative bodies does not limit its usability for actors at multiple levels. National scores can be used as starting points for negotiations and reforms by civil society organisations. Ratings can be made prerequisites for international socio- economic agreements to ensure compliance with labour standards, similar to EU’s GSP+ and USA’s GSP, which require compliance in law and practice with specific labour standards in order to avail certain trade benefits through reduced tariffs. The Index provides meaningful input into policy discussions to improve labour market protections at the country level.

The Labour Rights Index is also a useful benchmarking tool that can be used in stimulating policy debate as it can help in exposing challenges and identifying regulatory best practices. The Index provides meaningful input into policy discussions to improve labour market protections at the country level. The Labour Rights Index is a repository of “objective and actionable” data on labour market regulation along with the relevant best practices which can be used by countries worldwide to initiate necessary reforms. The comparative tool can also be used by Labour Ministries for finding legislative best practices within their own regions and around the world.

The Labour Rights Index can work as an efficient aid for workers as well to gauge the labour rights protections in laws across countries. With increased internet use, the availability of reliable and objective legal rights information is the first step towards compliance. The Labour Rights Index helps in achieving that step. The Index is similarly useful for national and transnational employers to gauge their statutory obligations in different workplaces and legal settings.

It can be used as a benchmarking tool for policy making. While the Index does not promote “legislative transplants”, it shows the international recommended standard based on UN or ILO Conventions and Recommendations. Similarly, the Index does not advocate the idea of “one size fits all”; rather, countries may provide certain rights through statutory means or allow negotiation between the parties at a collective level.

Linkage with SDGs

In September 2015, 193 states decided to adopt a set of 17 goals to end poverty and ensure decent work as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Each goal has specific targets to be achieved over 15 years. There are 169 targets and 232 indicators listed under these 17 SDGs. The Labour Rights Index aims at an active contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals[1] by providing necessary (complementary) insights into de jure provisions on issues covered in particular by SDG 8 (Decent Jobs), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 16 (Strong Institutions).

The inextricable yet dormant link between decent work and economic growth has had a special trajectory with respect to development goals.

Unlike the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), where full employment and decent work were addressed through the inclusion of a new target (Target 1B[2]) in 2007 (six years after the start of the MDGs in 2001), Goal 8 under the SDGs focuses on the promotion of inclusive and sustainable economic growth that leads to employment and decent work for all[3]. This has not necessarily resulted in a positive response. The linking of economic growth and decent work under Goal 8 has been criticised as the relegation of decent work – a human rights concern – to being a mere dividend of economic growth[4].

Despite this criticism, owing to the global financial crisis of 2008 and the current COVID-19- induced labour market crisis, employment and work has gained centre-stage. Employment and employment-related issues are also referred to in other goals[12].

Target 8.8 refers explicitly to the protection of labour rights and promotion of safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants and those in precarious employment. While Target 8.8 talks about the protection of all labour rights, Indicator 8.8.2 is solely concerned with national compliance with freedom of association and collective bargaining rights.

There is no doubt that the freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining are enabling rights. These not only have a direct bearing on labour and economic outcomes but also help in guaranteeing democracy in a country. The 2014 Nobel Prize to Tunisia’s National Dialogue Quartet, especially to The Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), was a testimony of labour support to democracy after the Jasmine Revolution.[13] The Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) was one of the four organisations that were awarded the Nobel Prize.

However, as required under Target 8.8, the protection of labour rights has to be holistically ensured, including for those in precarious employment, the most recent form of which is the gig economy. Instead of focusing only on trade union rights, all workplace rights can and should be measured and monitored both in law and practice.

The Labour Rights Index also covers the regulation of the gig economy as one of the evaluation criteria and gives a positive score to a country where gig workers are not treated as merely independent contractors.

No country or state has enacted comprehensive legislation to protect the rights of these precarious workers. The scoring methodology, however takes into account access to basic social protection, i.e., old age benefits, invalidity benefits and survivors’ benefits, for independent contractors. The majority of the countries give access to basic social protection to independent contractors.

Despite their unprecedented status,[14] SDGs indicators were not ascertained through conventional global consultations. These were finalised by a select group of experts in March 2017.[15] The implementation and achievement of Target 8.8 depend on the availability of data on labour laws and labour practices. Various indices have targeted the latter or a combination of the two. The Labour Rights Index attempts to make a distinctive contribution by being one of the few that focus on the former.

Significant work in this sphere exists in the form of few ILO databases[16] and some indices like the World Bank’s Employing Workers database[17], the Women, Business and Law Database[18], the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (Labour Market Efficiency Pillar)[19], the Harvard/ NBER Global Labour Survey[20], the Index of Economic Freedoms (Labour Freedom component)[21] and the International Social Security Association (ISSA)[22], the OECD Indicators of Employment Protection[23], and the CBR-LRI (CBR Labour Regulation Index)[24]. While the International Labour Organisation is the lead agency for indicator 8.8.2, some work is already in progress on the issue.

Each of the mentioned surveys deals with specific aspects concerning labour rights. The ITUC[25] Survey on Violations of Trade Union Rights covers trade union rights.[26], the ITUC Global Rights Index, contrary to its name, measures only trade union rights using nearly 97 indicators.[27] Similarly, The Centre for Global Workers’ Rights under Penn State University has worked on the Labour Rights Indicators measuring compliance both in law and practice for freedom of association and rights to collective bargaining through 108 indicators.[28] The same indicators or evaluation criteria have been proposed by the ILO for measuring progress under SDG Indicator 8.8.2.

Despite this glut of indices on labour rights, experts at the WageIndicator Foundation and the Centre for Labour Research[29] have been working on the idea of a new de jure index, i.e., the Labour Rights Index. While various targets under SDG 8 focus on statistical data, none of those targets and indicators delves into the de jure labour rights protections as required under Target 8.8.

Based on 10 indicators and 46 evaluation criteria, the Index compares labour legislation[30] in 135 countries. There is no other comparable work in scale and scope on labour market regulations.

The 10 indicators cover the following aspects: fundamental workers’ rights (the right to unionise and the elimination of employment discrimination, child labour and forced labour), fair wages, decent working hours, employment security, social protection (access to the living wage, unemployment, old age, disability and survivor benefits and health insurance), work-life balance for workers with family responsibilities and access to safe and healthy workplaces. All index components are grounded in and linked with a selected list of international conventions and covenants.

The work is essentially based on ten substantive elements which are closely linked to the four strategic pillars of the Decent Work Agenda, that is, (i) Core labour standards and fundamental principles and rights at work (ii) Employment creation (iii) Social protection and (iv) Social dialogue and tripartism. The ILO Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalisation 2008 has emphasised that the four strategic objectives of the Decent Work Agenda are “inseparable, interrelated and mutually supportive. The failure to promote any one of them would harm progress towards the others”.[31]Based on the recommendation of the 2008 ILO Declaration to establish appropriate indicators to monitor and evaluate the progress achieved, the ILO adopted a framework of statistical and legal Decent Work Indicators.

The framework indicators cover the ten substantive elements of the Decent Work Agenda. These elements are:[32]

- employment opportunities

- adequate earnings and productive work

- decent working time

- combining work, family and personal life

- work that should be abolished (child labour and forced labour)

- stability and security of work

- equal opportunity and treatment in employment

- safe work environment

- social security

- social dialogue, employers’ and workers’ representation

The Index is further built on the Decent Work Checks, which have detailed explanations of de jure provisions on various workplace rights under national labour law. None of the above-referred indices is as comprehensive and detailed as the Labour Rights Index.

While many would argue against building another index focusing only on de jure labour market institutions and provisions (namely, due to the existence of large informal sectors in developing countries, non-compliance coupled with the tepid and lacklustre implementation of labour laws), well-drafted and inclusive laws are still a precondition for attaining decent work. Well-drafted laws provide clear and explicit answers to difficult and perplexing questions.

The results and insights from the comparative Labour Rights Index can be used to bring much-needed labour legislation reforms in various countries. Universal labour guarantees or basic labour protections should be available to everyone. This essentially means that all workers, regardless of their contractual arrangement or employment status, should enjoy fundamental workers’ rights (freedom of association and right to collective bargaining, non-discrimination, no forced or child labour), an adequate living wage, maximum limits on working hours, safety and health at work, and access to the social protection system. The Index will not only help reform and develop missing legal provisions but will also help in tracing the jurisprudential evolution of legal systems in one of the most impressionable legal spheres.

Progress on Target 8.8, requiring protection of labour rights for all workers, including those in precarious employment, can be measured only through the comprehensive Labour Rights Index. Given the labour market havoc wreaked by the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years,[33] this is the most opportune time to address the protection of all labour rights and measure the progress of member countries.

In the words of the California Attorney General, Xavier Becerra, “Sometimes it takes a pandemic to shake us into realising what that [lacking basic labour protections] really means and who suffers the consequences.”[34] It is time to measure every country’s progress on all labour protections instead of merely focusing on trade union rights under SDG Indicator 8.8.2.

Data Notes

The WageIndicator Foundation and the Centre for Labour Research have developed the Labour Rights Index, which looks at the status of countries in terms of providing laws related to decent work for the labour force. The data set covers 10 indicators for 135 countries. The Index aims to provide a snapshot of the labour rights present in the legislation of the countries covered.

The following assumptions have been used while constructing the Labour Rights Index. The worker in question

- Is skilled;[35]

- Is at least a minimum wage worker; Resides in the economy’s most populous province/state/area;

- Is a lawful citizen or a legal immigrant[36] of the economy;

- Is a full-time employee with a permanent contract in a medium-sized enterprise with at least 60 employees;

- Has work experience of one year or more;

- Is assumed to be registered with the relevant social security institution and for a long enough time to accrue various monetary benefits (maternity, sickness, work injury, old age pension, survivors’, and invalidity benefit); and

- Is assumed to have been working long enough to access leaves (maternity, paternity, paternal, sick, and annual leave) and various social benefits, including unemployment benefits.

Methodology

The subtopics in a Decent Work Check (DWC)[37] have been used to structure 46 questions under the indicators in constructing this Index. However, what differentiates the Labour Rights Index from the Decent Work Checks is that it is more specific, adds newer topics like pregnancy inquiry, comparison between minimum age for employment and compulsory schooling age, and scoring of trade union questions is not solely dependent on labour legislation in the country. Forty-six data points are obtained across 10 indicators, each containing four to five binary questions. Each indicator represents an aspect of work which is considered important for achieving decent work.[38] The scores for each indicator are obtained by computing the unweighted average of the answers under that indicator and scaling the result to 100. The final scores for the countries are then determined by taking each indicator’s average, where 100 is the maximum score to achieve. Where an indicator has four questions, each question/component has a score of 25.

Where an indicator has five questions, each question/component has a score of 20. A Labour Rights Index score of 100 would indicate that there are no statutory decent work deficits in the areas covered by the Index.

Conceptual Framework

The Index consists of ten elements disaggregated into 46 components. These indicators and their components are presented below. Detailed description for each component can be found in the section on Indicators for Decent Work.

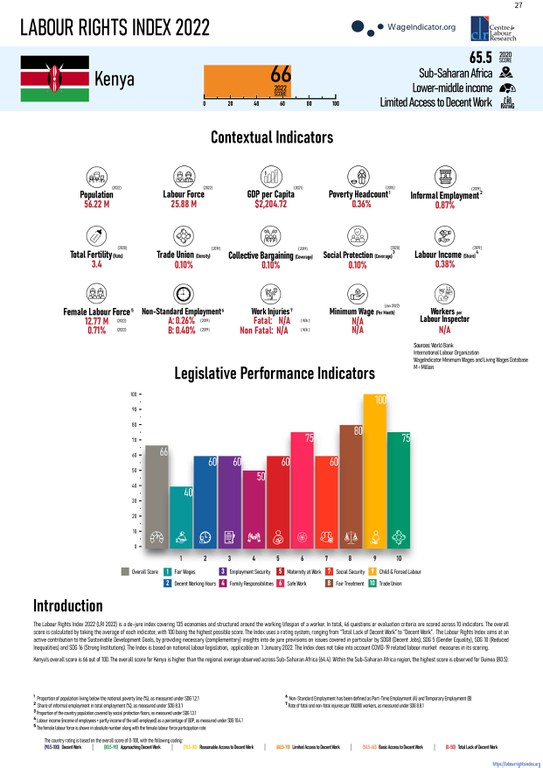

To illustrate the scoring process in the Index, Kenya, for example, receives a score of 100 under the indicator of Child and Forced Labour. This signifies that the country has legal protections in place for young workers participating in the labour market. However, under the indicator of Family responsibilities, Kenya scores 50 since the legislation does not guarantee parental leave and flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities.

Scoring along these lines for a country, the overall score of Kenya is determined by taking the unweighted average of the scores for all 10 indicators on a 0-100 scale, where 0 represents the worst regulatory performance and 100 the best regulatory performance in the labour market. The overall score for Kenya is 66. For a comparison with other countries, please refer to the overall scores table at the start of this report.

The labour legislation of the 135 countries, applicable on 1 January 2022, is the source of information used to answer questions in the Labour Rights Index. The Index does not take into account COVID-19-related labour market measures initiated by countries. Strengths and limitations exist with this approach. While the Labour Rights Index has been designed to be an easily replicable tool to benchmark countries, there are certain advantages and limitations. To ensure comparability of data across 135 economies, specific assumptions have been made. The indicators in the Index are based on standardised assumptions to make the laws comparable across countries. For instance, an assumption used for this Index is that the worker in question who is affected by the labour laws has experience of one year or more at a workplace, as questions on annual leave and severance pay can only apply to this kind of worker. Hence, workers with temporary contracts of a duration of less than one year may not have access to such rights.

Another assumption underlying the Index is that the focus is on the labour legislation, which applies to the most populous province/state/area of a country.

This allows the Index to give a more accurate depiction of a country’s labour rights as the labour laws affect most of its population, even though the legislation affecting workers in areas with lower populations may be different.

Furthermore, the Index is also based on labour legislation which applies to the formal economy in the private sector. Despite more than 60 per cent of the global workforce in need of transitioning from informal to the formal economy,[39] focusing on the labour laws affecting the formal sector retains attention on the sector since the labour laws in the formal economy are more applicable and that is the ultimate goal. ILO Recommendation 204 also recommends gradual transition from the informal to the formal economy through the enactment of necessary legislation and reduction of barriers to transition. Focusing on the formal economy and its applicable legislation also indicates the kind of rights that will be available to the informal economy workers on successful transition to the formal economy.

Other than statutes, the Labour Rights Index also considers general or inter-professional collective agreements applicable at the national level. For countries where minimum wages are determined through collective bargaining, sectoral agreements (for major economic sectors) can also be considered.

Strengths and Limitations of the Labour Rights Index

| Feature | Strength | Limitation |

| Standardised assumptions | Makes labour legislation comparable across countries and methodology uncomplicated | Limits legislation under review |

| Focus on workers having one year or more at a workplace | Allows maximum coverage of labour rights | Does not consider the rights of casual and temporary workers. Non-standard workers may not have access to some of the workplace rights and components under the Labour Rights Index |

| Coverage of most populous province/state/area | Makes labour legislation comparable across countries where different areas have different labour laws for their populations; Gives a more accurate picture of a country’s labour rights | Can decrease representativeness of labour rights where differences in laws across areas exist |

| Focus on the formal economy | Retains attention on the formal sector where labour laws are more applicable | Does not cover the rights of the workforce in the informal economy, which could have a substantial part of the labour force in some countries |

| Use of codified national labour legislation only | Allows actionable indicators since the law can be changed by policymakers | Where lack of implementation of labour legislation, making changes solely in the law will not gain the desired outcome; Does not consider socio-cultural norms |

Moreover, this report acknowledges the presence of gaps between legislation and its practice. For instance, gaps could stem from the lack of implementation of laws because of poor enforcement, weak design, or limited capacity.

Still, observing differences in legislation helps give a clearer understanding of where labour rights may be limited in practice.

This study also recognises the presence of social, economic and cultural factors affecting the practice of legal rights. For example, women may not be working at night, although legally allowed, as social and cultural norms could restrain such options. Or a lack of safe transport may limit women’s employment during night hours.

Poverty-stricken areas may have children under the minimum working age being employed for long hours and not in light work. Workers may be doing overtime exceeding the weekly hour limit because the culture at their organisations may view such workers as harder working and thus more deserving of a reward.The Labour Rights Index 2022 acknowledges the restraints of its standardised assumptions and focuses on codified law. Even if these assumptions do not cover all the labour force in the country, they ensure the comparability of data.

Unlike other indices, the Labour Rights Index does not consider ratification of international conventions in its scoring or rating system since mere ratification is not a good indicator of actual implementation of international labour standards. It uses the standards prescribed in these Conventions (e.g., 14 weeks of maternity leave or the minimum age for hazardous work as 18 years) and scores countries on that basis.

All the 10 indicators and 46 evaluation criteria of the Labour Rights Index are grounded in substantive elements of the Decent Work Agenda. The legal basis for all components (regulatory standards) emanates from the UN or ILO Conventions. Table explains in detail these legal sources.

In summary, the Labour Rights Index methodology has various useful features. The methodology:

- Is transparent and based on facts taken directly from codified laws.

- Uses standardised assumptions for data collection, thereby making logical comparisons across countries.

- Allows data to identify the labour rights and their presence (or lack of) in the legislation of 135 countries.

International Regulatory Standards and Labour Rights Index

| Indicators and Components | Source of the Regulatory Standard | |

| 1. Fair Wages | ||

| 1 | Minimum wage (statutory or negotiated) | Article 23 (3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 3 of Minimum Wage Fixing Convention 1970 (No. 131); Article 7 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social & Cultural Rights (Fair Wage clauses) |

| 2 | Regular wage | Article 12 (1) of Protection of Wages Convention 1949 (No. 95); Article 11 (6) and 12 of Social Policy (Basic Aims and Standards) Convention 1962 (No. 117) |

| 3 | Overtime premium (≥125%) | Article 6 of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 7 of the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1930 (No. 30) |

| 4 | Weekly rest work compensation (time-off) | Article 5 of the Weekly Rest (Industry) Convention, 1921 (No. 14); Article 8 (3) of the Weekly Rest (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1957 (No. 106)[1] |

| 5 | Night work premium | Article 8 of Night Work Convention, 1990 (No. 171) |

| 2. Decent Working Hours | ||

| 6 | General working hours (≤48 hours per week) | Article 2 of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 3 of the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1930 (No. 30); Article 1 of the Forty-Hour Week Convention, 1935 (No. 47) |

| 7 | Maximum working hours (≤56 hours per week) | Para 17 of the Reduction of Hours of Work Recommendation, 1962 (No. 116); Article 6 (2) of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 7 (3) of the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1930 (No. 30) |

| 8 | Weekly rest (≥24 hours) | Articles 3-6 of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 2 of Weekly Rest (Industry) Convention 1921; Article 6 of Weekly Rest (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1957 |

| 9 | Paid public holidays | Article 5 of Working Conditions (Hotels and Restaurants) Convention 1991 (No. 172); Article 6 (1) of Holidays with Pay Convention (Revised) 1970 (No. 132); Article 7 (c) of the Part-Time Work Convention, 1994 (No. 175) |

| 10 | Annual leave (≥3 working weeks) | Article 3 of Holidays with Pay Convention (Revised) 1970 (No. 132) |

| 3. Employment Security | ||

| 11 | Written employment contract | Articles 7-8 of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189); Part II (5) of the Private Employment Agencies Recommendation, 1997 (No. 188) |

| 12 | Fixed term contract (≤5 years) | Article 2 (3) of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158); Article 3 (2) of the Termination of Employment Recommendation, 1982 (No. 166) |

| 13 | Probation period (≤3 months) | Article 2 (b) of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158) |

| 14 | Termination notice period (1 month) | Article 11 of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158) |

| 15 | Severance pay (≥14 days per year of service) | Article 12 of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158) |

| 4. Family Responsibilities | ||

| 16 | Parental leave | Article 1 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156); Paragraph 22 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Recommendation, 1981 (No. 165); Paragraph 10 of the Maternity Protection Recommendation, 2000 (No. 191) |

| 17 | Paternity leave (≥1 week) | 2009 ILC Resolution Concerning Gender Equality at the Heart of Decent Work |

| 18 | Flexible working arrangements | Article 1 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156); Paragraph 18 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Recommendation, 1981 (No. 165); Article 9 (2) of the Part-Time Work Convention, 1994 (No. 175) |

| 19 | Nursing breaks | Article 10 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 5. Maternity at Work | ||

| 20 | Prohibition on inquiring about pregnancy | Article 9 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 21 | Maternity leave (≥14 weeks) | Article 4 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); Article 11 (2) of UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) |

| 22 | Cash maternity benefits (≥66.67% of former wage) | Article 6 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 23 | Source of maternity benefits (social insurance or state financing) | Article 6(8) of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 24 | Protection from dismissals (pregnancy/maternity) | Article 8 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); Article 11 (2) (a) of UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) |

| 6. Safe Work | ||

| 25 | Personal protective equipment (free of cost) | Article 16 and 21 of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) |

| 26 | Training on health and safety | Article 19 (d) of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) |

| 27 | Restriction on work (prejudicial to health of mother or child) | Article 3 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 28 | Employment injury benefits | Part VI of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 7. Social Security | ||

| 29 | Old age pension | Part V of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 30 | Survivors’ pension | Part X of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 31 | Unemployment benefits | Part IV of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 32 | Sickness benefits (≥ 6 months) | Part III of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 33 | Invalidity benefits | Part IX of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 8. Fair Treatment | ||

| 34 | Prohibition of employment discrimination | Article 2 of the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111); Articles 8 and 9 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); Article 4 of the Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (Disabled Persons) Convention, 1983 (No. 159); Article 1 of the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98); Article 5 and 27 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| 35 | Equal remuneration for work of equal value | Article 2 of the Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100) |

| 36 | Prohibition of sexual harassment | Article 7 of the Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (No. 190) |

| 37 | Absence of restrictions on women’s employment | Article 2 of the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111) |

| 38 | Basic labour protections for gig workers | Global Commission on the Future of Work 2019[2]; Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), 2017 |

| 9. Child and Forced Labour | ||

| 39 | Prohibition on child labour (<15 years) | Article 2 of Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138); Article 32 (2) of the Convention on Rights of Child |

| 40 | Age (employment entry ≥ compulsory schooling) | Article 2(3) of Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138) |

| 41 | Prohibition on hazardous work for under 18 | Article 3 of Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138); Article 32 (1) of the Convention on Rights of Child |

| 42 | Prohibition on forced labour | Article 2 of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29); Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, 1930; Article 8 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

| 10. Trade Union | ||

| 43 | Right to unionise | Article 2 of the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87) |

| 44 | Right to collective bargaining | Article 4 of the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98), Article 2 of the Collective Bargaining Convention, 1981 (No. 154) |

| 45 | Right to strike | Para 751, Compilation of Decisions of the Committee on Freedom of Association, 2018 |

| 46 | Prohibition on replacing striking workers | Article 1 of the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98) |

Data Sources and Collection

While the Index is essentially based on Decent Work Checks, the Index has at least 20 new countries for which Decent Work Checks are yet to be developed. For all countries, labour legislation, including various decrees, amendments and collective agreements, was revisited to score each component and provide a direct legal basis. The legal basis has been provided in individual country profiles. The cut-off date for all data collection is 1 January 2022. Any legislation or change in the law that occurs after said date, where the effective date is set later than 1 January 2022, or where the effective date is not yet precisely known, is not reflected in the Index.

However, the situation in individual countries might have shifted.

The Scoring System

We use a dichotomous scoring system for the 46 indicators (1 for a yes and 0 for a no).

Non-binary scores (such as a scale of 1 to 5) introduce difficulties in defining meaningful and comparable standards or guidelines for each score. This can lead to arbitrary, erroneous and incomparable scores. For example, a 2 for one country may be a 3 for another, and so on.

Alternatively, an expert may find a country- specific indicator that differs from another country. This violates a fundamental principle of measurement known as reliability – the degree to which a measurement procedure produces accurate measurements every time, regardless of who performed it.

Weights

The Labour Rights Index does not use weights. Each indicator features either four or five underlying components framed as questions. Every component contributes equally to the indicator, and every indicator contributes equally to the overall score. The overall score (from 0-100) is calculated from a simple unweighted average of scores from 10 indicators.

As pointed out at the outset, the indicators and components of the Labour Rights Index cover the employment lifecycle of a person. Consider the example of annual leave and sick leave. While annual leave is accessed by a greater percentage of workers every year compared with sick leave, giving them weights (whether equal or unequal) would be arbitrary and would not serve the purpose.

Similarly, consider the example of child labour and forced labour questions. While the majority of workers may not have to experience these menaces, it is a harsh reality for many, at least in developing countries. Giving weights would mean prioritising one component over the other.

Countries at different stages of development may also have different legal provisions. For example, as is evident throughout the study, work-life balance and gender equality related legislation is also linked with economic development. With certain exceptions, most high-income countries have instituted provisions on paternity leave and parental leave.

If these components are given higher weightage than the other, developing countries’ scores will be comparatively much lower.

Greater weightage to certain areas of labour law can create an inherent bias and also lead to the agents’ skewed efforts to initiate reforms in areas with higher weights. Countries will inherently target laws with greater weightage.

If giving weights were an option, fundamental principles and rights at work would be given higher weights. These are freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour; the effective abolition of child labour; the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation, and a safe and healthy working environment.[40]

Even before the amendment of the 1998 Declaration in 2022, ILO had started giving importance to other workplace rights. The 2019 Declaration notes that “all workers should enjoy adequate protection following the Decent Work Agenda, taking into account:

- respect for their fundamental rights;

- an adequate minimum wage, statutory or negotiated;

- maximum limits on working time; and

- safety and health at work.”

Similarly, social protection, or social security (both terms are used interchangeably), is enshrined as such in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966). ILO Recommendation 202 suggests that countries should establish and maintain national social protection floors as a nationally defined set of basic social security guarantees that secure protection to prevent or alleviate poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion.

Hence, instead of preferring one component or indicator over the other, the Labour Rights Index has been developed without assigning weights.

Ranking

Similarly, the Labour Rights Index does not “rank” countries.

The ordinal ranking method (for example, “first”, “second”, and “third”) is problematic as it leads to the naming and shaming of countries at the bottom of the list. Moreover, as argued by the World Bank’s Doing Business Report in 2016, rankings may encourage the agents (countries being ranked) to “game the system”.[41] There is a risk that the agents may divert a disproportionate amount of resources and efforts to the areas which are measured/scored while leaving aside areas which are equally important but not scored. To deal with this issue, the Labour Rights Index does not use ordinal ranking, although it covers the whole gamut of labour rights.

The Index does not aim at producing a single number in the form of ranking. Rather it gives a run down on the local labour legislation, supported by detailed Decent Work Checks, updated annually.

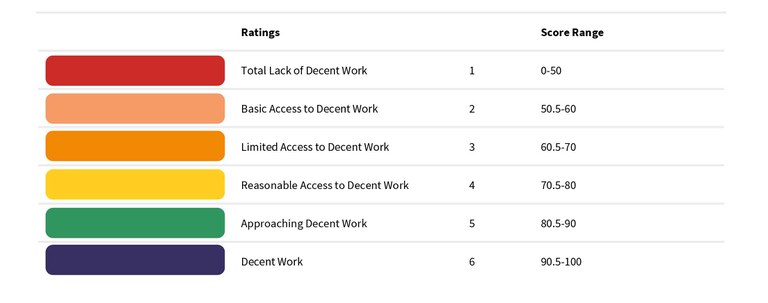

The Labour Rights Index, however, does place 135 countries into six categories and rates these from “Decent Work” to “Total Lack of Decent Work”. [42]

Description of the Ratings

1 - Total Lack of Decent Work

Decent work deficits are rife in countries with a rating of 1 (Total Lack of Decent Work). The national/local legislation barely meets the international standard on even half of the 46 evaluation criteria. There is an absence of minimal labour rights under the legislation. Workers are deprived of access to decent work in nearly every aspect of working life.

2 - Basic Access to Decent Work

Minimal labour rights are provided under the legislation in countries with a rating of 2 (Basic Access to Decent Work). There are systematic violations of workplace rights through statutory means. Workers have nominal access to decent work in a few aspects of working life only. The national/local legislation does not meet the international standard on nearly 20 of the 46 evaluation criteria.

3 - Limited Access to Decent Work

Restricted labour rights are provided under the legislation in countries with a rating of 3 (Limited Access to Decent Work). Workers have access to decent work in limited aspects of working life only. The national/local legislation does not meet the international standard on nearly 18 of the 46 evaluation criteria.

4 - Reasonable Access to Decent Work

Generally, labour rights are reasonably provided under the legislation in countries with a rating of 4 (Reasonable Access to Decent Work). Workers have fair access to decent work in some aspects of working life. The countries with this rating have scored Yes on at least 33 of the 46 evaluation criteria.

5 - Approaching Decent Work

Countries with a rating of 5 (Approaching Decent Work) have generally a lower level of labour rights than those with a rating of 6. Countries with this rating have scored Yes on at least 37 of the 46 evaluation criteria. Most labour rights are provided under the legislation. Workers have frequent access to decent work in most aspects of working life.

6 - Decent Work

Almost all labour rights, as covered by the Index, are provided under the legislation in countries with a ranking of 6(Decent Work). Workers have regular access to decent work in nearly every aspect of working life. Reforms in labour legislation in a couple of areas can improve the statutory rights further.

What is Next?

In the upcoming editions of the Labour Rights Index, we plan to include the following components: Provision of daycare/childcare centres at the workplace; fair treatment of part- time workers equivalent to comparable full-time workers with respect to different aspects of employment; the labour inspection system; prohibition of worst forms of child labour; establishment of social dialogue or tripartite mechanism to discuss labour market issues at the economy level.

The establishment of a vibrant labour inspection system and social dialogue mechanism with due representation from all relevant stakeholders is important from a governance viewpoint. While these are not directly associated with workers’ rights, these make the attainment of workers’ rights easier by simplifying the processes and removing any institutional hurdles.

It is also planned to extend the coverage to 145 countries. These mainly include countries from Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and some South American countries. Any future legal updates which lead to changes in the scores will also be included.

How to Read the Country Profiles

The Country Profiles section shows a two-page profile for each of the 135 countries covered in the Labour Rights Index 2022. The country profiles are informative about the major aspects of labour legislation in an economy.

Performance Overview

In this section, the performance of a country in the Labour Rights Index is illustrated. On the top right of the page, the overall average score (out of 100) and rating (out of six categories) give a snapshot of a country’s standing in the Labour Rights Index. The top right of the page also shows the overall score in 2020, along with region and income group information.

The overall scores benchmark countries with respect to regulatory best practices, as identified in the relevant ILO Conventions, thereby indicating the proximity to the regulatory standard on each component. Each country is allocated ratings according to its overall score. The ratings follow a certain coding; [90.5-100] Decent Work (Blue), [80.5- 90] Approaching Decent Work (Green), [70.5-80] Reasonable Access to Decent Work (Yellow), [60.5- 70] Limited Access to Decent Work (Orange), [50.5- 60] Basic Access to Decent Work (Peach), [0-50] Total Lack of Decent Work (Red).

The Contextual Indicators of the country provide a picture of the economy and its labour force at a glance. These facts include Population, Labour Force, GDP per Capita, Poverty Headcount, Informal Employment, Total Fertility rate, Trade Union Density, Collective Bargaining Coverage, Social Protection Coverage, Labour Income Share, Female Labour Force (absolute number and participation rate), Non-Standard Employment (Part-Time Employment-A and Temporary Employment-B), Work Injuries (Fatal and Non-Fatal), Minimum Wage, and number of Workers per Labour Inspector. The contextual indicators have been sourced from International Labour Organization, World Bank data, and the WageIndicator’s own Minimum Wages Database.

The first page also introduces the Index and gives information about the average regional score and the highest scoring country in the region.

The overall score and each of the indicators are denoted by different colours; Overall score (Grey), Fair Wages (Teal), Decent Working Hours (Blue), Employment Security (Violet), Family Responsibilities (Purple), Maternity at Work (Red), Safe Work (Pink), Social Security (Orange), Fair Treatment (Brown), Child & Forced Labour (Yellow), Trade Union (Green). To read about the scoring methodology, refer to the chapter on Indicators for Decent Work.

The second page of the country profile shows the decent work indicators of the Labour Rights Index and the answer for each component, along with its legal basis. It is a step toward ensuring greater transparency in the scoring of the countries. The last column shows the trend over the previous two years (2020 to 2022); if the score increased due to a positive reform, it decreased due to a legislative reform or if the score was adjusted to increased availability and access to more legal information about the country. A total of 46 components are shown under the 10 indicators for each of the 135 countries in the Labour Rights Index.

The end of the second page also shows Covid-19 and labour market related information about the country. The data on covid cases, deaths and vaccinations is as on 19 July 2022 and is taken from Our World in Data.[43] The labour market and social protection measures are sourced from the February 2022 edition of the World Bank study, “Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real- Time Review of Country Measures”.[44]

It must, however, be mentioned that for data regarding COVID-19 and labour market regulations and COVID-19 cases in countries, we have mostly relied on World Bank and Our World in Data, respectively. It can be the case that in countries with good protection of sick leave, job security and the like, the laws also protect against COVID-19, yet this is not reflected in the data from the World Bank. The information regarding COVID-19 and labour issues does not affect the countries scoring and rating. If you have any questions about a country and the data provided, please contact the team.

Sample Country Profile

Kenya

Country profiles for all 135 countries are available for download on http://labourrightsindex.org/