Acknowledgements

The Wagelndicator Foundation and the Centre for Labour Research co-produced the first edition of the Labour Rights Index in 2020. The second edition was released in October 2022, and it included 135 countries. This is the third edition of the Labour Rights Index, covering 145 countries.

WageIndicator Foundation (Amsterdam), established in 2001, collects, compares and shares labour market information through online and offline surveys and research. Its national websites serve as always up-to-date online libraries featuring (living) wage information, labour law and career advice, for employees, employers and social partners. In this way, WageIndicator is a life changer for millions of people around the world. The WageIndicator works towards increased transparency in labour markets by providing access to minimum wages, living wages, and labour rights information.

The Centre for Labour Research, an independent non-profit registered in Pakistan, has a niche speciality in comparative labour research. Other than advising the federal and provincial government in Pakistan on labour issues, the Centre is the Wagelndicator's global Labour Law Office and maintains the Labour Law Database and Minimum Wages Database.

As explained in the first version, the Labour Rights Index is the culmination of more than 15 years of comparative labour law work by Iftikhar Ahmad, who has spearheaded this report. The work has benefited from valuable inputs from the Wagelndicator Foundation.

The team gratefully acknowledges Wagelndicator for their input and continuous support. Paulien Osse, Dirk Dragstra and Kea Tijdens reviewed the report and made valuable suggestions. In addition, feedback from Fiona Dragstra (Director Wagelndicator), Daniela Ceccon (Director Data, Wagelndicator), Professor Beryl ter Haar (University of Leiden), Professor Elena Sychenko (University of Bologna) and Asghar Jameel (Centre for Labour Research Board) helped refine the Index and its methodology. We are grateful to Diletta Porcheddu (ADAPT) and Michele Dalla Sega (ADAPT) for confirming labour law data for France and Italy. Shantanu Kishwar (WageIndicator) has supported simplifying the methodology for a better understanding of non-experts.

We are also grateful to all the organisations from which we source the key facts that are part of the country profiles.

These include the World Bank, the International Labour Organization and the Wagelndicator Foundation.

The scoring for country profiles under different indicators, though essentially hinged on the Decent Work Checks, have also been confirmed from other indices/reports, including the Women, Business and Law Database (World Bank), International Social Security Association (ISSA) Country Profiles, various ILO databases, the US Department of State's Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (USDOS CRHRP), the US ILAB Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labour, the ITUC Global Rights Index and the Centre for Global Workers' Rights. Our special thanks and appreciation go to the International Labour Organization, whose instruments (conventions and recommendations) are part of our scoring methodology: the country scoring has been based on these instruments as much as possible. The comments and observations of the ILO supervisory body, the Committee of Experts on Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR) were considered while scoring the indicator on Freedom of Association. Similarly, the US Department of State's Country Reports on Human Rights Practices have also been used to score freedom of Association questions.

Special thanks are due to the team members at the Centre for Labour Research who have worked long hours for months to produce this work. Iftikhar Ahmad has led the legal research, the methodology behind the Index, the scoring of countries and the drafting of the report. Seemab Haider has done outstanding work in designing heatmaps, country profiles and the 2024 report. Both Seemab Haider and Shanza Sohail have been part of the Labour Rights Index since its inception in 2020. Tasmeena Tahir has made exceptional contributions and has been involved in the entire process of the index, ranging from the collection of contextual indicators to legal research and reviewing the legal basis for countries.

We extend our sincere gratitude to our whole team for their tireless efforts to bring this report to fruition. In addition to their contributions to drafting, scoring, and conducting legal research, Ambreen Riaz and Razan Ayesha have provided invaluable support to all team members. Sobia Ahmad reviewed the scores and did a quality check of the data along with reviewing the report design. Ayesha Kiran and Ayesha Mir have supported the work by maintaining the Minimum Wages Database and Labour Rights Database, respectively.

Scoring is done by the Wagelndicator/Centre for Labour Research team comprising Iftikhar Ahmad, Shanza Sohail, Tasmeena Tahir, Ambreen Riaz and Razan Ayesha.

Sidharth Rath has created an informative video about the Labour Rights Index 2024, with a voiceover from Dirk Dragstra. The Labour Rights Index heat map has been developed by Seemab Haider. Special thanks to Paulien Osse and Gunjan Pandya for bringing the heat map and country profiles online.

The Index, heat map, and country profiles are available at: https://labourrightsindex.org.

Team Behind the Index

Iftikhar Ahmad (Team Lead) |

|||

Core Team

|

Technical Support Team

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

COUNTRY LEVEL CONTRIBUTORS

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|||

Foreword

With a great deal of pride, we at the WageIndicator Foundation are excited to launch the third edition of the Labour Rights Index in 2024. The Labour Rights Index is unique in its ambition and scope, now scoring labour laws in 145 countries relative to the Decent Work Agenda of the International Labour Organisation.

Though an invaluable source of knowledge, the Labour Rights Index’s impact goes further - it forms the basis of WageIndicator’s DecentWorkCheck survey. We use this survey to assess compliance with and awareness of labour laws in garment factories, flower farms, and factories in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya. These survey findings have helped trade unions negotiate improved wages, safety standards, working hours and more for their workers, showing that the Index can tangibly benefit workers and create fairer workplaces world-over.

This latest edition of the Labour Rights Index also comes at an important moment. Since we launched the second edition in October 2022, several countries have changed labour laws to benefit workers.

West Asian countries have reformed the Kafala system that came under scrutiny in the wake of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, and we see changes in national labour law after the EU passed the Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions. Gender equality has been a prominent theme in reforms since 2020, with 16 countries passing reforms to enable equal access for women to the same jobs as men, 14 improving paternity leave, and 4 improving maternity leave provisions, just to name a few.

All of these developments point to an important and positive pattern - contrary to beliefs that globalised supply chains would lead manufacturing nations to weaken labour laws to attract investment, there is no race to the bottom in this domain. Instead, there seems to be a collective recognition that fair and equal workplaces are the foundation of stable societies and supply chains. Though there is still a long way to go in seeing these ambitions become reality both in letter and spirit, there are positive signs that we are on the right trajectory.

We hope that this 2024 edition of the Labour Rights Index can contribute to this cause, and provide you with the information you need for your work, your research, your advocacy campaign, your policy paper, or simply broadening your understanding of

labour laws in a comparative perspective.

Happy Decent Work Day!

Fiona Dragstra

Director WageIndicator Foundation

Copyright and Disclaimer

Copyright © 2024 by WageIndicator Foundation (Netherlands) and Centre for Labour Research (Pakistan)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below.

WageIndicator Foundation - www.wageindicator.org

WageIndicator Foundation is an independent non-profit organisation. It develops, operates and owns national WageIndicator websites with labour-related content, using data from its WageIndicator Salary and Working Conditions Survey, Minimum Wages Database, Collective Agreement Database, Salary Checks and Calculations, Decent Work Checks and related Labour Law Database, and Cost of Living Survey and resulting Living Wages Database.

The mission of WageIndicator is to promote labour market transparency for the benefit of all employers, employees and workers worldwide by sharing and comparing information on wages, labour law and careers. WageIndicator does so by making this information freely available on national WageIndicator websites in the national language(s). WageIndicator now has operations in 208 countries.

Centre for Labour Research - www.clr.org.pk

Centre for Labour Research, a non-profit organisation registered in Pakistan under section 42 of the Companies Act 2017, works on comparative labour issues. Besides its advisory work with the federal and provincial governments in Pakistan, the Centre is the WageIndicator Global Labour Law Office. The Centre creates the Decent Work Checks and maintains the WageIndicator Labour Law Database and WageIndicator Minimum Wages Database.

Bibliographical Information

WageIndicator Foundation and Centre for Labour Research (2024), Labour Rights Index 2024. Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Islamabad, Pakistan, October.

© WageIndicator Foundation and Centre for Labour Research 2024. All rights reserved. For queries and feedback, please write to us at office@wageindicator.org

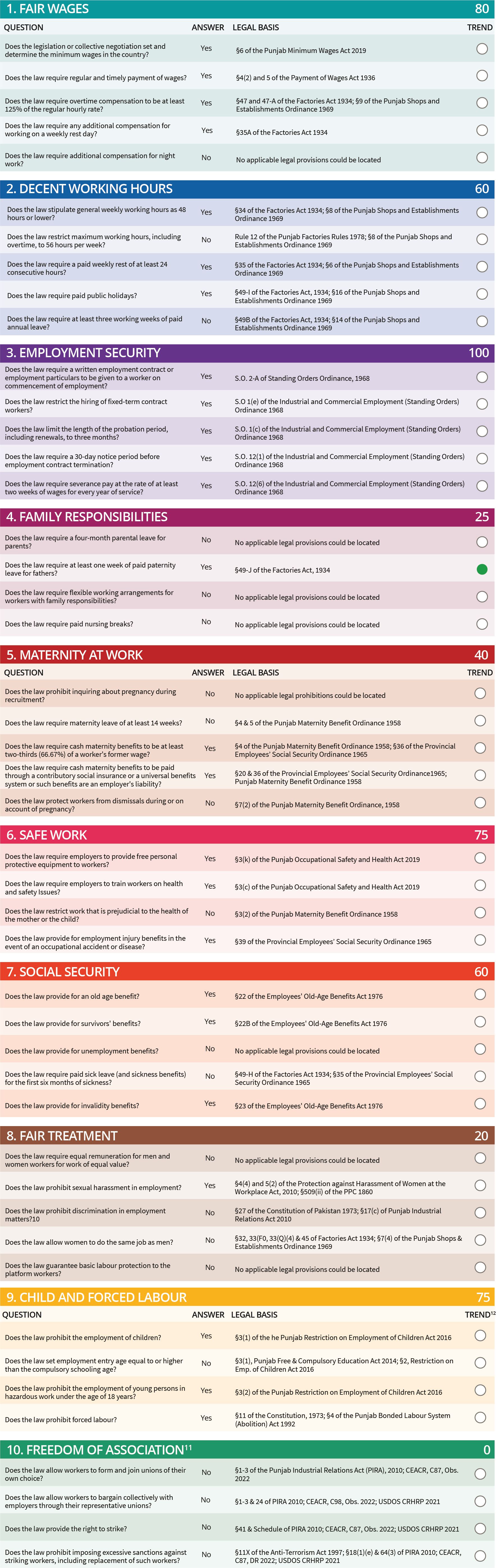

Disclaimer 1: The maps used in this report are sourced from AM Charts and may not reflect the political ground realities. For reference, please see https://www.amcharts.com/

Disclaimer 2: The Labour Rights Index is based on comprehensive research by WageIndicator Foundation and the Centre for Labour Research. Every humanly possible effort has been made to refer to the correct legal source and score a country accordingly. However, there might be cases where scoring does not reflect the actual legislation. This could be either because we could not locate such legislation or there was a mistake in scoring. If you find such a case, please write to us at: office@wageindicator.org.

Credits: Photos used in the section on "Indicators for Decent Work" are sourced from Pexels and are free to use. Photo credits are given at end of each photo.

Section 1 INSIGHTS

Reforms Around The World

Summaries of Reforms

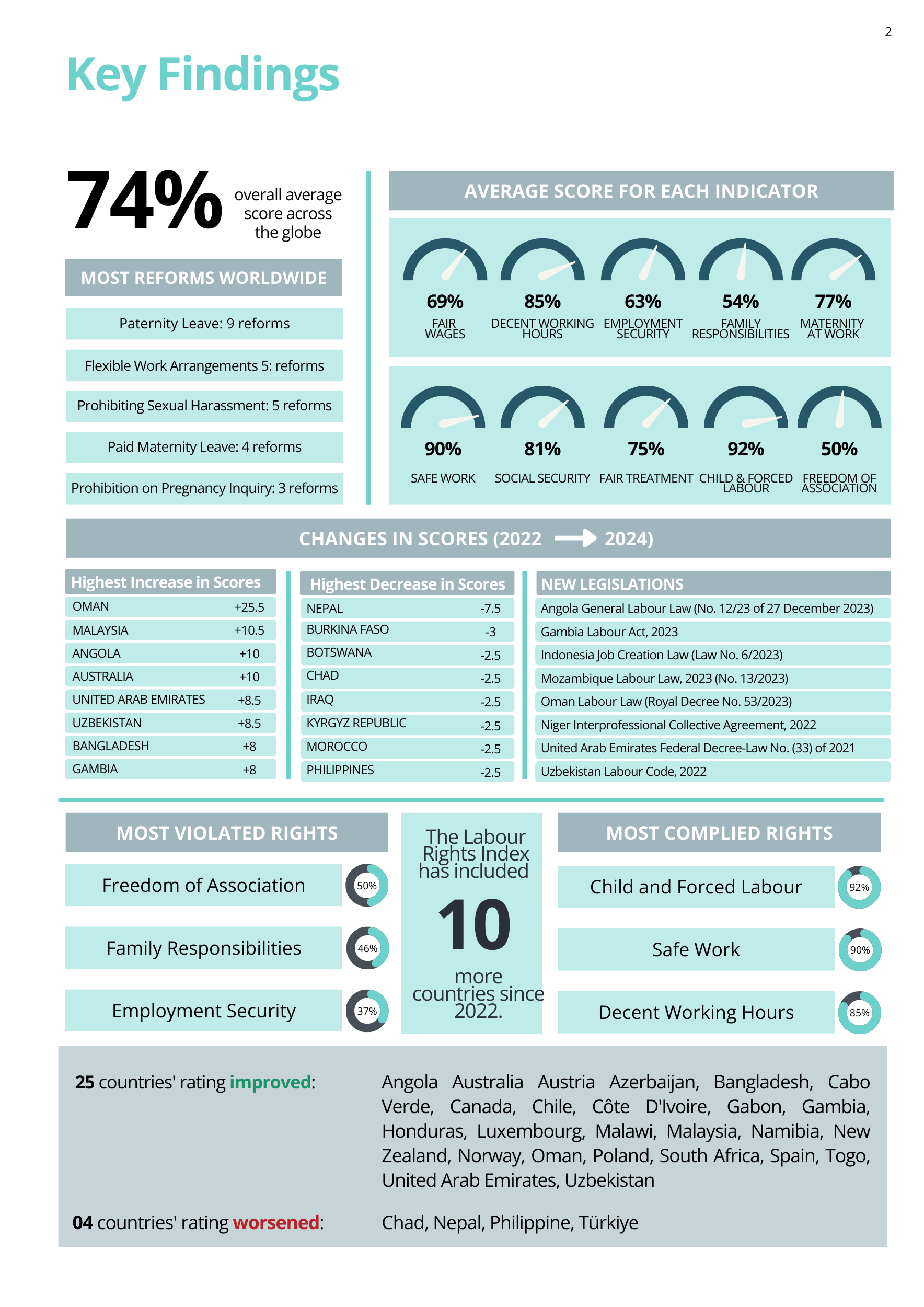

Between 1 January 2022 and 1 January 2024, we recorded 99 Changes to indicator scores. There were more than 70 instances where around 30 countries introduced positive legal reforms, resulting in a change of score on a component to 1. In 20 cases, scores improved because 20 countries revised their minimum wages during the last two years (after 1 January 2022). These countries had earlier not updated their minimum wages during the period of 1 January 2020-1 January 2022.

Over the same period, we identified 8 instances where countries either introduced legislative changes or did not revise their minimum wages during the last two years, resulting in a change in their score to 0. Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Mozambique were the only countries to have introduced changes in their legislation that frustrated workers' rights, thereby affecting the provision of labour rights in these countries.

Algeria

❌ Fair Wages: Algeria did not revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Freedom of Association: Algeria has removed restrictions on workers’ right to form and join unions of their own choice.

Angola

✔ Fair Wages: Angola has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Employment Security: Angola has restricted the hiring of fixed-term contract workers by limiting the length and renewals of fixed-term contracts to 60 months.

✔ Maternity at Work: Angola has explicitly prohibited inquiring about pregnancy during recruitment.

✔ Maternity at Work: Angola has extended the length of the maternity leave from 13 to 17 weeks.

Australia

✔ Employment Security: Australia has restricted the hiring of fixed-term contract workers by limiting the maximum length, including renewals, of fixed-term contracts to 24 months.

Azerbaijan

✔ Fair Treatment: Azerbaijan has removed restrictions on women’s employment. The law now allows women to work in the same jobs as men.

Bangladesh

✔ Fair Wages: Bangladesh has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Social Security: Bangladesh has introduced contributory old-age pension and contributory survivors’ pension for its workers.

✔ Fair Treatment: Bangladesh has introduced the Suraksha scheme for self-employed by the National Pension Authority under the Universal Pension Management Act, 2023.

Benin

✔ Fair Wages: Benin has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Burkina Faso

✔ Fair Wages: Burkina Faso has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

Cabo Verde

✔ Family Responsibilities: Cabo Verde has introduced a paid paternity leave of 11 calendar days for fathers. Earlier, it had only 2 days of paternity leave.

Cameroon

✔ Fair Wages: Cameroon has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Chile

✔ Decent Working Hours: Chile has restricted maximum working hours to 52 hours per week, including overtime. The general working hours have been reduced from 45 to 40 hours per week.

Congo

✔ Maternity at Work: Congo has enacted a reform that explicitly prohibits inquiring about pregnancy during recruitment.

Fair Treatment: Congo now prohibits sexual harassment in employment with criminal penalties.

Costa Rica

✔ Family Responsibilities: Costa Rica has introduced a paid paternity leave of 8 calendar days for fathers.

Côte D'Ivoire

✔ Fair Wages: Côte D'Ivoire has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Cyprus

✔ Fair Wages: Cyprus has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

Egypt

✔ Fair Wages: Egypt has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

El Salvador

❌ Fair Wages: El Salvador has not revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Child and Forced Labour: El Salvador sets employment entry age equal to or higher than the compulsory schooling age. The minimum age for employment and compulsory schooling age is 16 years.

Estonia

✔ Family Responsibilities: Estonia now requires flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities.

Gambia

✔ Fair Wages: Gambia mandates the regular and timely payment of wages to all workers. Employment Security: Gambia requires severance pay at the rate of more than two weeks' wages for each year of service.

✔ Family Responsibilities: Gambia has introduced paid nursing breaks of one hour per day, starting after the end of maternity leave and lasting for 18 months.

✔ Maternity at Work: Gambia implicitly prohibits inquiring about pregnancy during recruitment by introducing pregnancy as one of the prohibited grounds for discrimination.

✔ Fair Treatment: Gambia has mandated equal remuneration for work of equal value. The country also prohibits discrimination in employment matters on at least seven of the ten grounds used in the “Discrimination in Employment” component.

Guinea

✔ Fair Wages: Guinea has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

Haiti

✔ Fair Wages: Haiti has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

Indonesia

❌ Decent Working Hours: Indonesia allows maximum working hours, including overtime, to extend up to 58 hours per week rather than limiting these to 56 hours.

✔ Fair Treatment: Indonesia now prohibits sexual harassment in employment with criminal penalties.

Ireland

✔ Family Responsibilities: Ireland now requires flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities.

Jordan

✔ Fair Treatment: Jordan now prohibits sexual harassment in employment with criminal penalties. A 2023 amendment in the Jordanian labour law removed restrictions on the working of women in different occupations.

Kenya

✔ Fair Wages: Kenya has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Kyrgyz Republic

❌ Child and Forced Labour: The employment entry age in the Kyrgyz Republic is lower than the compulsory schooling age since the Education law has set the compulsory schooling age as 17 years while the employment entry age is 16 years.

Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos)

✔ Fair Wages: Laos has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Lesotho

✔ Fair Wages: Lesotho has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Libya

✔ Fair Wages: Libya has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Luxembourg

✔ Family Responsibilities: Luxembourg now requires flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities.

Malawi

✔ Social Security: Malawi has introduced state-administered old-age, survivors’ and invalidity benefits for its workers and their families.

Malaysia

✔ Family Responsibilities: Malaysia has introduced a paid paternity leave of 7 calendar days for fathers.

✔ Maternity at Work: Malaysia has extended the length of maternity leave from 8.5 weeks to 14 weeks. The country now also protects workers from dismissals during or on account of pregnancy.

✔ Fair Treatment: Malaysia now prohibits Sexual harassment in employment with civil remedies. The country has also removed restrictions on women’s employment. The law now allows women to work in the same jobs as men.

Malta

✔ Family Responsibilities: Malta has introduced a paid paternity leave of 10 working days for fathers. The country also requires flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities.

Mozambique

✔ Family Responsibilities: Mozambique has introduced a paid paternity leave of 7 calendar days for fathers

✔ Freedom of Association: Mozambique has lifted restrictions on the right to strike for workers.

❌ Freedom of Association: Mozambique does not prohibit employers from terminating employment contracts of striking workers.

Myanmar

✔ Fair Wages: Myanmar has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

Niger

✔ Fair Wages: Niger has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Employment Security: Niger has reduced the length of the probation period, including renewals, from six months to a maximum of two months.

Nigeria

✔ Fair Wages: Nigeria has updated its minimum wages during the last two years.

Oman

✔ Employment Security: Oman has restricted the hiring of fixed-term contract workers by limiting the length of fixed-term contracts, including renewals, to 60 months.

✔ Family Responsibilities: Oman has introduced 365 days of parental leave for parents and 7 calendar days of paid paternity leave for fathers. The country has also introduced paid nursing breaks of one hour per day, starting after the end of maternity leave and lasting for 12 months.

✔ Maternity at Work: Oman has extended the length of maternity leave from 7.1 (50 days) to 14 weeks (98 days), and the maternity benefits are now paid through social insurance or the universal benefits system.

✔ Safe Work: Oman has restricted work that is prejudicial to the health of the mother or the child. Social Security: Oman has introduced state-administered unemployment benefits for its workers as well as state-administered sickness benefits during the first 6 months of sickness for its workers.

✔ Freedom of Association: Oman has lifted all restrictions on the right to bargain collectively with employers through their representative unions. The country also prohibits the replacement or termination of the striking workers.

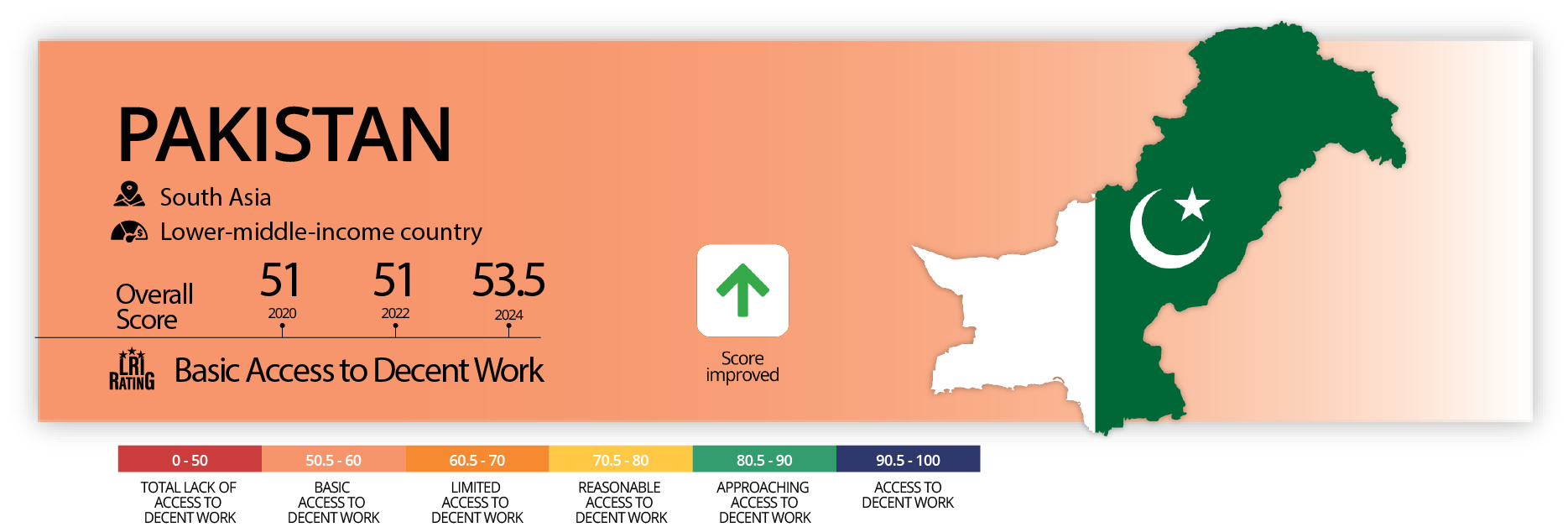

Pakistan

✔ Family Responsibilities: Pakistan has introduced a paid paternity leave of 7 calendar days for fathers.

Papua New Guinea

❌ Fair Wages: Papua New Guinea did not revise its minimum wages during the last two years.

Peru

✔ Fair Wages: Peru has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

Qatar

❌ Fair Wages: Qatar did not revise its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Fair Treatment: Qatar has introduced voluntary coverage protection for self-employed workers, which includes gig workers.

Rwanda

✔ Family Responsibilities: Rwanda has introduced a paid paternity leave of 7 calendar days for fathers

✔ Maternity at Work: Rwanda has extended the length of maternity leave from 12 to 14 weeks. The country also protects workers from dismissals during or on account of pregnancy.

Slovakia

✔ Family Responsibilities: Slovakia has introduced a paid paternity leave of 196 days for fathers. Slovakia now also requires flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities.

Sri Lanka

❌ Fair Wages: Sri Lanka did not revise its minimum wages during the last two years.

Togo

✔ Fair Wages: Togo has revised its minimum wages during the last two years.

✔ Maternity at Work: Togo now protects workers from dismissals during or on account of pregnancy.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

✔ Decent Working Hours: UAE has restricted maximum working hours, including overtime, to 56 hours per week provided that the maximum working hours cannot exceed 144 hours for every 3-week period.

❌ Employment Security: UAE requires less than 30 days’ notice before employment contract termination.

✔ Social Security: UAE has introduced state-administered unemployment benefits for its workers. Fair Treatment: UAE now prohibits discrimination in employment matters on at least seven of the ten grounds specified in the methodology of the Index.

✔ Fair Treatment: UAE has introduced voluntary coverage protection for self-employed workers.

✔ Child and Forced Labour: UAE prohibits the employment of children in hazardous work under the age of 18 years.

Uzbekistan

✔ Decent Working Hours: Uzbekistan now grants workers the right to enjoy more than three working weeks of paid annual leave.

✔ Fair Treatment: Uzbekistan has also removed restrictions on women’s employment. The law now allows women to work in the same jobs as men.

✔ Freedom of Association: Uzbekistan has removed restrictions on workers’ right to form and join unions of their own choice. The country has also lifted all restrictions on the workers’ right to bargain collectively with employers through their representative unions.

Zimbabwe

✔ Fair Treatment: Zimbabwe has mandated equal remuneration for work of equal value.

Global Trends in Labour Rights

The Labour Rights Index tracks the changes in workplace rights during the past two years. However, some countries have enacted regressive and repressive labour legislation, undermining and frustrating workers' rights.

The section describes some major trends before delving into detail at the country level.

Minimum Wages

As per the Labour Rights Index 2024, approximately 94% of (136 of the 145) countries have established statutory or negotiated minimum wage provisions. While two countries (Singapore and South Sudan) lack any minimum wage regulations, seven countries set minimum wages exclusively for nationals or for public sector employees. All 10 newly added countries have statutory minimum wage systems; however, only eight of those revised their minimum wages during the last two years. However, thirty- three countries have received negative scores due to the fact that, despite having statutory minimum wages, these wages have not been revised in the past two years. A notable advancement in this regard is the recent implementation of a non- discriminatory minimum wage policy in Jordan in 2023, following Qatar's introduction of a similar measure in 2020. This policy ensures that all workers, regardless of nationality (or migration status), receive equal minimum wage protection.

Maternity leave

In 2024, a review of 145 countries under the Labour Rights Index revealed that 102 of these countries offer a statutory maternity leave entitlement of 14 weeks. Of the remaining countries, only 14 provide less than 12 weeks of maternity leave, while 29 countries provide maternity leave of 12-13 weeks. This indicates that maternity leave is widely recognised as a fundamental right. In the contemporary world, the primary focus has shifted from whether paternity leave is available to ensuring that maternity leave is accompanied by adequate maternity benefits. Nonetheless, it is essential to implement legislation to prevent employers from imposing disadvantages, such as termination or discrimination due to pregnancy. During the last two years, Angola, Cabo Verde, Malaysia, Oman, Rwanda and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have increased their maternity leave from previous levels though the maternity leave is still lower than 14 weeks in Cabo Verde and the UAE.

Paternity Leave

Paternity leave has experienced an upward trend over the past two years. At the time of scoring for the Labour Rights Index (LRI) 2022, only 59 countries provided a statutory right to paid paternity leave of at least seven calendar days for fathers at childbirth. This number has increased to 71 countries in 2024. This rise is partly attributed to the addition of 10 new countries to the index in 2024, among which 4 offer at least seven days of paid paternity leave. Nine countries that did not provide paternity leave in 2022 have now enacted necessary reforms requiring paid paternity of at least seven calendar days. These nine countries are spread across Africa (Cabo Verde, Mozambique, and Rwanda), Asia (Malaysia, Oman and Pakistan), Europe (Malta and Slovakia), and Latin America (Costa Rica).

Additionally, a significant number of countries (35) provide between 1-5 days of paid paternity leave, while the remainder either offer no leave (74 countries) or provide it on an unpaid basis (7 countries). Paternity leave is increasingly gaining traction among legislators, especially in the EU, as societies adapt to the realities of the modern world, where both parents often participate in the workforce. Iran and Oman are the only countries in the MENA region that require paid paternity leave of at least 7 calendar days. Such provisions facilitate a better balance between work and family responsibilities and promote a more equitable distribution of caregiving duties between men and women.

Pregnancy Testing

Though international regulatory standards (C183) prohibit requiring women workers to take pregnancy tests, with a few exceptions related to occupational risks to the worker's or child's health, there are 63 countries where the practice is not prohibited under legislation. Since 2022, Angola, Congo, and Gambia have prohibited pregnancy testing or inquiring about pregnancy during recruitment. This allows women to join the workforce rather than being stopped at the door. Moreover, nine of the ten newly added countries, Ecuador, Eswatini, Georgia, Moldova, North Macedonia, Sierra Leone, Taiwan, and Tajikistan, either implicitly or explicitly prohibit inquiring about pregnancy during recruitment.

Flexible Work Arrangements

According to the Labour Rights Index 2024, only 53 countries provide some form of flexible working arrangements for workers with family responsibilities. Of these, 34 are European countries. This prevalence is attributable to the EU Directive on Work-Life Balance for Parents and Carers, which grants all working parents of children up to at least 8 years old, as well as all carers, the right to request flexible working arrangements. These arrangements include reduced working hours, flexible working hours, and flexibility in the place of work.

European societies generally place a strong emphasis on achieving a balance between work and personal life, which has facilitated the widespread adoption of these flexible working arrangements. In contrast, such provisions are notably scarce in developing countries, where achieving a balance between work and family life remains a significant challenge. Even in developed countries outside of Europe, there is a marked disparity in the availability of flexible working arrangements, reflecting the broader emphasis European societies place on fostering work-life balance.

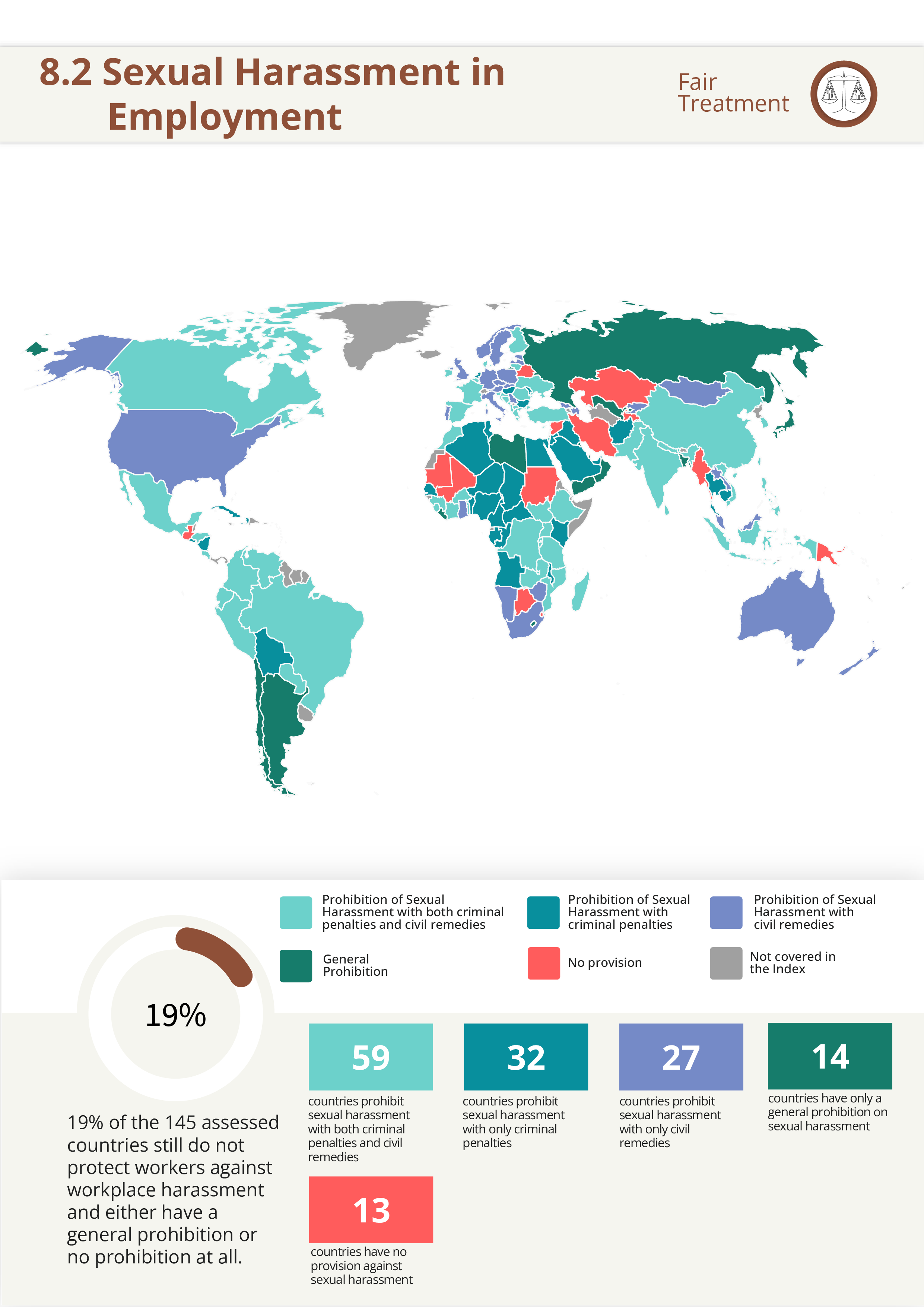

Sexual Harassment

According to the Labour Rights Index, over 80% (118 of the 145) of the countries have established statutory prohibitions against sexual harassment, accompanied by either criminal penalties or civil remedies. Thirteen countries have no provisions for addressing sexual harassment, while fourteen countries only have general prohibitions without any penalties. The implementation of robust sexual harassment laws is essential, as harassment frequently goes unaddressed or is not taken with the requisite seriousness. Enforcing penalties for sexual harassment is critical to ensuring that such conduct is properly deterred and addressed, thereby promoting safer and more respectful work environments. Congo, Indonesia, Jordan and Malaysia have enacted necessary reforms after 2022 to prohibit sexual harassment at work.

BEST COUNTRIES FOR WORKERS |

WORST COUNTRIES FOR WORKERS |

| Austria | Botswana |

| Azerbaijan | Eswatini |

| Belgium | Lebanon |

| Bulgaria | Nigeria |

| Czechia | Papua New Guinea |

| Denmark | Qatar |

| Finland | Singapore |

| France | Sri Lanka |

| Greece | Sudan |

| Hungary | |

| Italy | |

| Latvia | |

| Lithuania | |

| Luxembourg | |

| Moldova | |

| Norway | |

| Poland | |

| Portugal | |

| Romania | |

| Serbia | |

| Slovakia | |

| Spain | |

| Sweden |

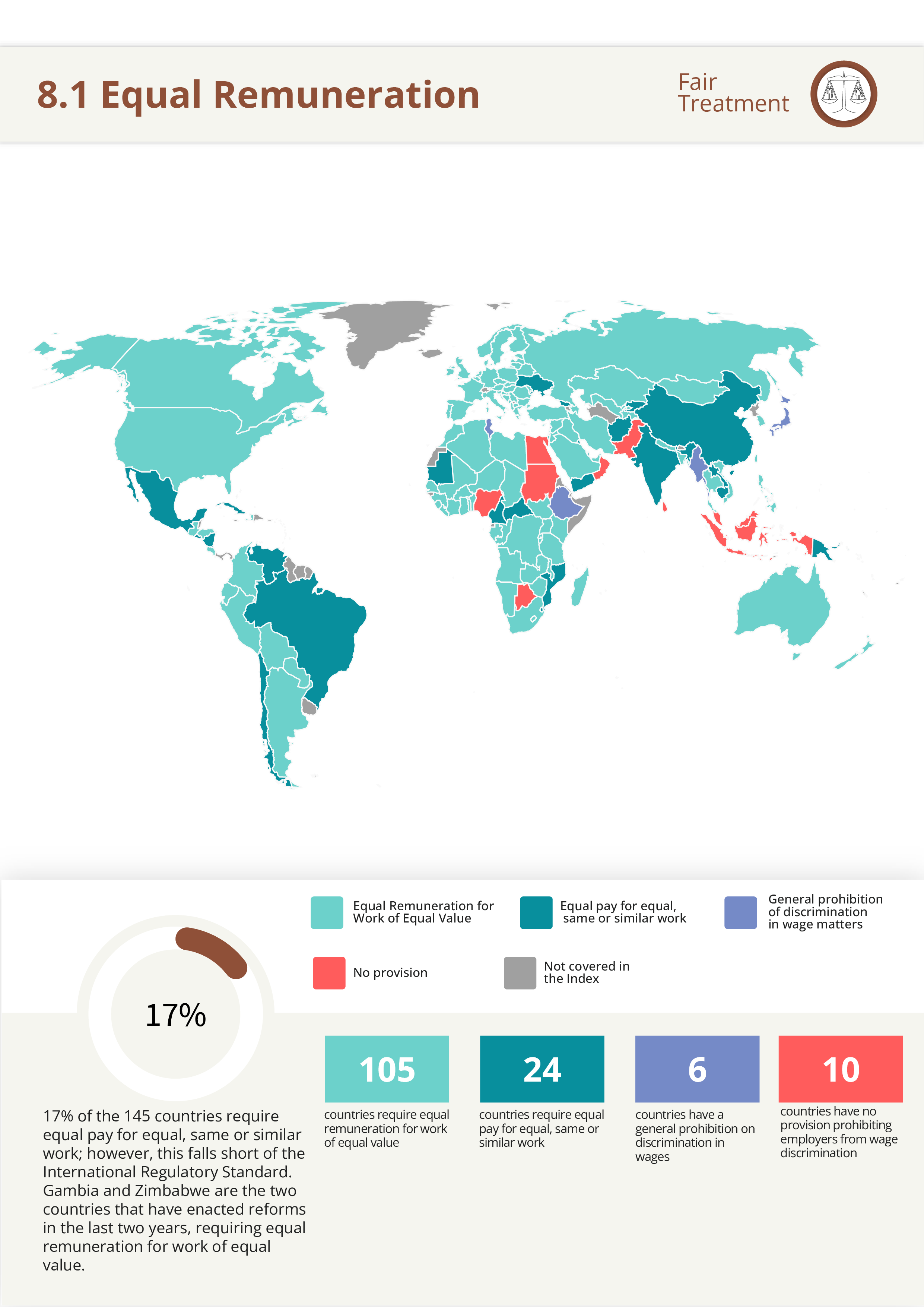

Equal Pay for Work of Equal Value

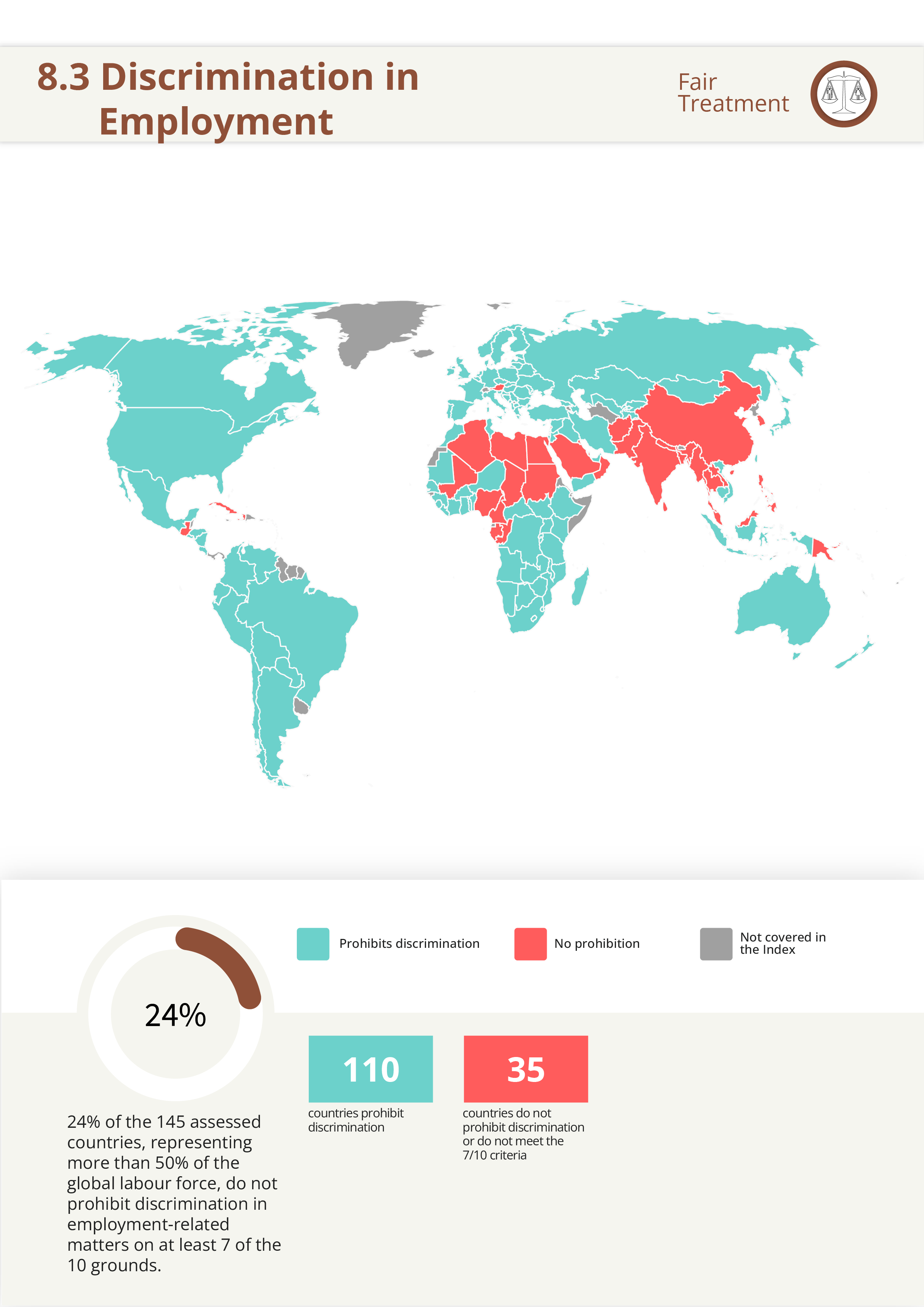

The gender wage gap, the difference between their earnings, expressed as a percentage of men's earnings, is a useful measure to indicate how far behind women are in terms of wages. Women earn, on average, significantly less than men. Globally, the gender wage gap currently stands on average at 23 per cent - meaning that women earn 77 per cent of what men earn for each hour worked. The pay gap is even wider for mothers, women of colour, immigrant women, and disabled women. Legislation requiring equal pay for work of equal value and mandating minimum living wages can help narrow the gender pay gap in a country. Twenty-four countries require equal pay for equal, same or similar work; however, these countries did not get a score since the legislative provisions do not meet the “equal remuneration for work of equal value” standard. scored Three countries, Gambia, Uzbekistan and Zimbabwe, have enacted reforms mandating equal pay for work of equal value.

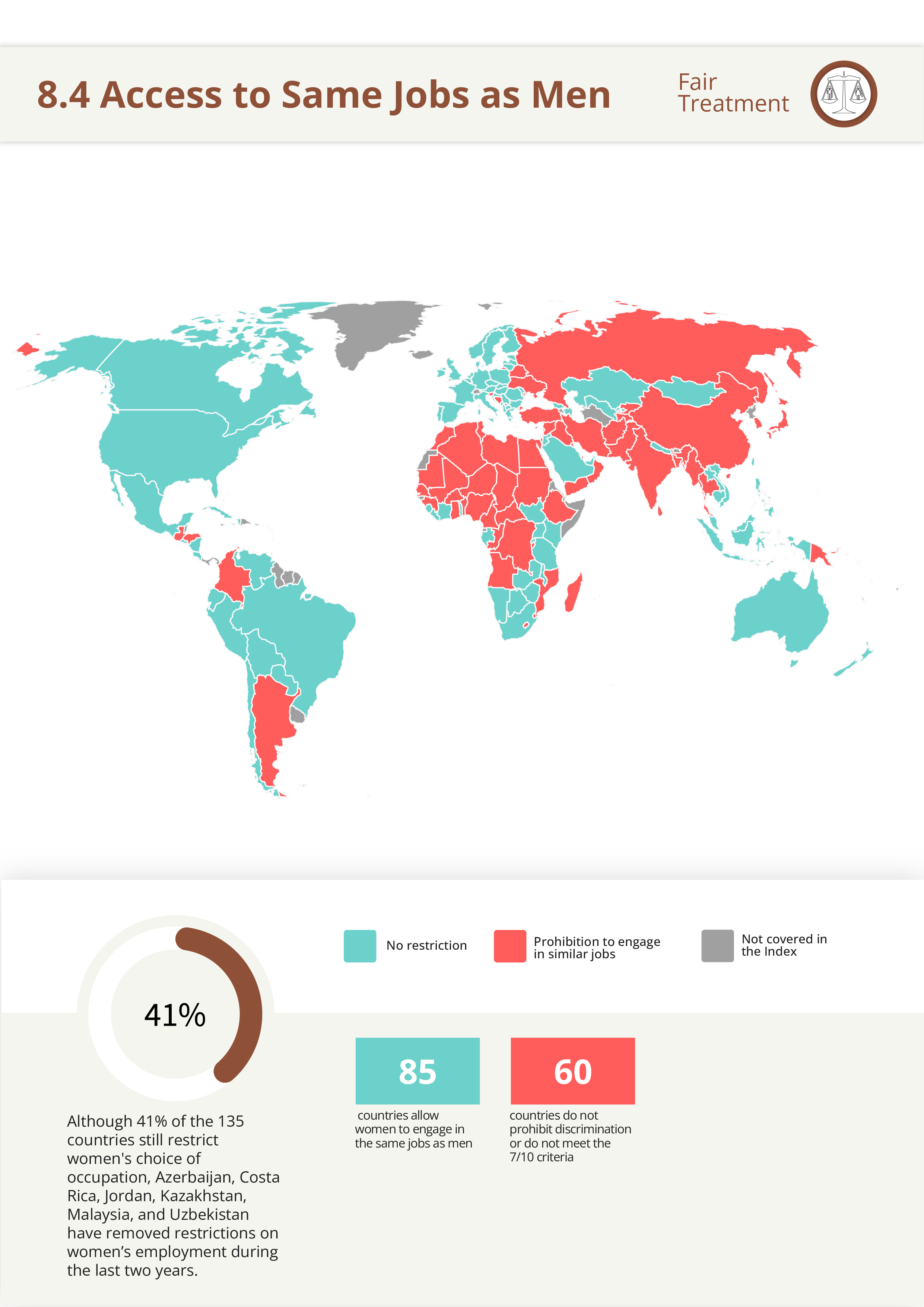

Women’s Access to Same Jobs as Men

In the Labour Rights Index 2024, it is reported that 85 countries have provisions ensuring women have access to the same job opportunities as men. However, labour legislation in nearly half of the countries assessed by the Index imposes restrictions on women’s access to certain occupations under the guise of protection. These restrictions often include prohibitions on night work, the designation of extensive lists of jobs as dangerous or hazardous for women, and bans on women’s employment in sectors such as mining, construction, certain factories, and transportation. Such legislative measures constrain employment opportunities for women, contributing to their concentration in lower-income and lower- productivity jobs. Azerbaijan, Costa Rica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, and Uzbekistan enacted reforms during the last two years, allowing women to work the same jobs as men.

Among the 10 new countries added to the Index, Ecuador, Georgia, Moldova, North Macedonia, Sierra Leone, and Taiwan have established provisions that ensure women have access to the same jobs as men.

Section 2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Introduction

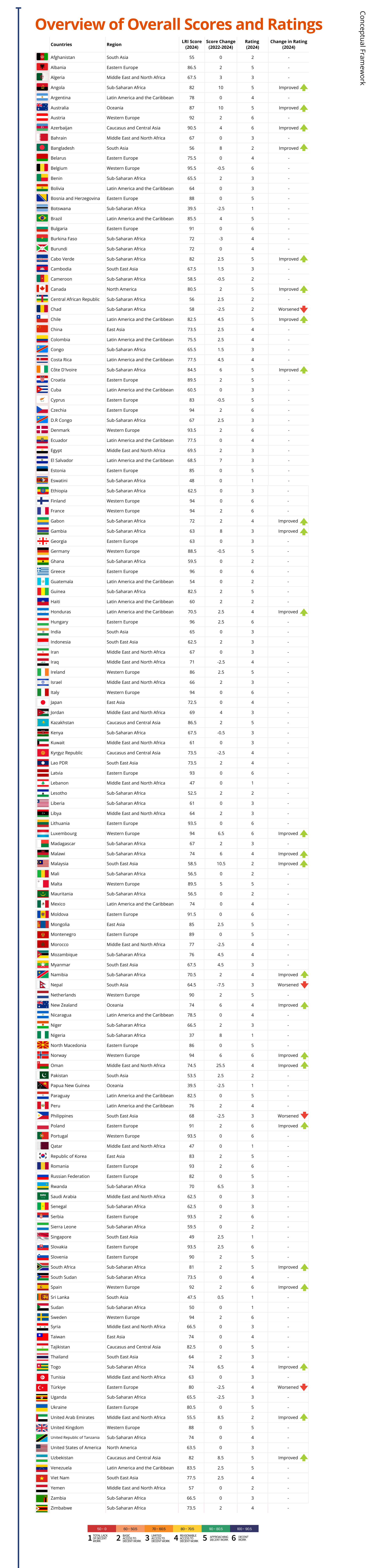

This is the third edition of the Labour Rights Index. Starting from 2020, the Index is released biennially. The first and second editions of the Index included 115 and 135 countries respectively.

The third edition of the Index has 145 countries and covers labour market regulation affecting approx. 95% of the global labour force (3.369 billion workers), especially the formal sector workers. Even when we consider the proportion of informal employment in total employment (58%) at the global level, the formal sector workers who are impacted by these labour regulations are above 1.5 billion.

Labour Rights Index is a wide-ranging assessment of labour market regulations in 145 countries. It focuses on de jure (according to law) aspects of the labour market. The report scores 145 economies on

10 areas of labour market regulation. These are referred to as indicators. There is no other comparable project in terms of scope. The Index sheds light on a range of differences in laws/regulations on 46 topics or components across

145 countries. The Index offers a comprehensive picture of the (legislative) obstacles that workers face globally to enter the labour market and remain in the workforce.

The Labour Rights Index, while one of the many[1] de jure indices, is arguably the most comprehensive one yet in the field of workers' rights, as it encompasses every aspect of the working lifespan of a worker and identifies the presence of labour rights, or lack thereof, in national legal systems worldwide. The Index measures decent work and provides detailed information on rights at work as well as the local legal framework for regulating the labour market.[2]

While grounded in SDG 8[3], the Labour Rights Index is a tool essentially directed at governments and international organisations. And even though the underlying document for this Index, i.e.,the Decent Work Check, is aimed mainly at workers and trade unions, the Index targets national-level organisations like government agencies, trade union federations and multilateral organisations such as the United Nations. This Index measures all labour rights protections that have been referred to in Target 8.8.[4] The Labour Rights Index emphasises the importance of a well- functioning legal and regulatory system in creating enabling conditions for the achievement of Decent Work.

As a corollary, it lays bare the adverse impact of lack of regulation or inadequate regulation on the smooth functioning of (a) labour market(s). The Index does recognise large implementation gaps due to a lack of adequate supporting frameworks, including strong enforcement mechanisms.

The 2010 World Social Security Report notes that even the widest and most expansive legal foundations cannot achieve the desired outcomes if these are not enforced and backed by sufficient resources. Nevertheless, strong legal foundations are a precondition for securing higher provisions and resources. There is not a single situation where a country provides generous benefits without a comprehensive legal basis.[5]

Similar points have been raised by Botero et al.[6] that formal rules, although different from "on the ground" situations, still matter a lot. Botero's work formed the basis of the Doing Business Indicators by the World Bank. Research indicates that in the absence of legislation, even the wealthiest country in the world, i.e., the United States of America, is unable to ensure decent working conditions for a majority of its citizens. As explained by Heymann and Earle[7] "laws indicate a state's commitment to its people, lead to change by shaping public attitudes, encourage government follow-up through inspection and implementation of the law and allow court action for enforcement."

As an international qualification standard, the primary focus of the Labour Rights Index on larger administrative bodies does not limit its usability for actors at multiple levels. National scores can be used by the civil society organisations as starting points for negotiations and initiation of reforms. Ratings can be made prerequisites for international socio- economic agreements to ensure compliance with labour standards, similar to EU's GSP+[8] and USA's GSP[9], which require compliance in law and practice with specific labour standards in order to avail certain trade benefits through reduced tariffs. The Index provides meaningful input into policy discussions to improve labour market protections at the country level.

The Labour Rights Index is also a useful benchmarking tool that can be used in stimulating policy debate as it can help in exposing challenges and identifying regulatory best practices. The Index provides meaningful input into policy discussions to improve labour market protections at the country level. The Labour Rights Index is a repository of "objective and actionable" data on labour market regulation along with the relevant best practices which can be used by countries worldwide to initiate necessary reforms. The comparative tool can also be used by labour ministries for finding legislative best practices within their own regions and around the world.

The Labour Rights Index can work as an efficient aid for workers as well to gauge the labour rights protections in laws across countries. With increased internet use, the availability of reliable and objective legal rights information is the first step towards compliance. The Labour Rights Index helps in achieving that step. The Index is similarly useful for national and transnational employers to gauge their statutory obligations in different workplaces and legal settings.

It can be used as a benchmarking tool for policy making. While the Index does not promote "legislative transplants", it shows the globally recommended standards based on UN or ILO Conventions and Recommendations. Similarly, the Index does not advocate the idea of "one size fits all"; rather, countries may provide certain rights through statutory means or allow negotiation between the parties at a collective level.

Linkage with SDGs

In September 2015, 193 states decided to adopt a set of 17 goals to end poverty and ensure decent work as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Each goal has specific targets to be achieved over 15 years. There are 169 targets and 231 indicators listed under these 17 SDGs.[10] The Labour Rights Index aims at an active contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals by providing necessary (complementary) insights into de jure provisions on issues covered in particular by SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Jobs), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 16 (Strong Institutions).

The inextricable yet dormant link between decent work and economic growth has had a special trajectory with respect to development goals. Unlike the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), where full employment and decent work were addressed through the inclusion of a new target (Target 1B[11]) in 2007 (six years after the start of the MDGs in 2001), Goal 8 under the SDGs focuses on the promotion of inclusive and sustainable economic growth that leads to employment and decent work for all.[12] Although SDG 8 merges two separate areas of economic growth and employment into a single SDG, it is important to remember that issues related to the world of work are already part of the 20230 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Employment and employment-related issues are also referred to in other goals, including SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 13 (Climate Action) & SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). The achivement of some of these goals, especially reduction of poverty (SDG 1), eradication of hunger (SDG 2) and reduction of inequality (SDG 10) are all dependent on SDG 8 where people are engaged in full and productive employment and decent work for all is ensured.

The Sustainable Development Goals also recognise the importance of legislation in achievement of SDGs. For example, we can consider the following targets and indicators:

- 5.c Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels

- 10.3 Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard

- 16.b Promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development

Target 8.8 refers explicitly to the protection of labour rights and promotion of safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants and those in precarious employment. While Target 8.8 talks about the protection of all labour rights, Indicator 8.8.2 is solely concerned with national compliance with freedom of association and collective bargaining rights. There is no doubt that the freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining are enabling rights.

However, as required under Target 8.8, the protection of labour rights has to be holistically ensured, including for those in precarious employment, the most recent form of which is the gig economy. Instead of focusing only on trade union rights, all workplace rights can and should be measured and monitored both in law and practice. The Labour Rights Index attempts to make a distinctive contribution by focusing on Target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers).

Significant work in this sphere exists in the form of few ILO databases[13] and some indices like the World Bank's Employing Workers database[14], the Women, Business and Law Database[15], the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Index (Labour Market Efficiency Pillar)[16] the Harvard/ NBER Global Labour Survey[17], the Index of Economic Freedoms (Labour Freedom component) [18] and the International Social Security Association(ISSA)[19] the OECD Indicators of Employment Protection[20], and the CBR-LRI (CBR Labour Regulation Index).[21]

Each of the mentioned surveys deals with specific aspects concerning labour rights. The ITUC Global Rights Index, measures trade union rights using nearly 97 indicators.[22] Similarly, The Centre for Global Workers' Rights under Penn State University has worked on the Labour Rights Indicators measuring compliance both in law and practice for freedom of association and rights to collective bargaining through 108 indicators.[23] The same indicators or evaluation criteria have been proposed by the ILO for measuring progress under SDG Indicator 8.8.2.

Despite this glut of indices on labour rights, experts at the Wagelndicator Foundation and the Centre for Labour Research[24] have been working on the idea of a new de jure index, i.e., the Labour Rights Index. While various targets under SDG 8 focus on statistical data, none of those targets and indicators delves into the dejure labour rights protections as required under Target 8.8. Based on 10 indicators and 46 evaluation criteria, the Index compares labour legislation[25] in 145 countries. There is no other comparable work in scale and scope on labour market regulations.

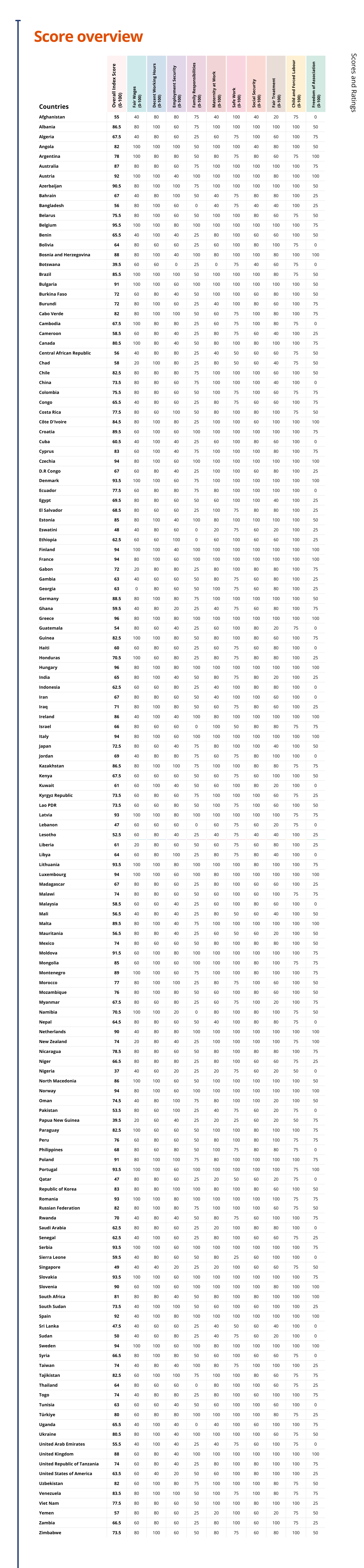

The 10 indicators cover the following aspects: fundamental workers' rights (the right to unionise and the elimination of employment discrimination, elimination of child and forced labour, and safe and healthy working environment), fair wages, decent working hours, employment security, social protection (access to the living wage, unemployment, old age, disability and survivor benefits and health insurance), and work-life balance for workers with family responsibilities. All index components are grounded in and linked with a selected list of international conventions and covenants.

The work is essentially based on ten substantive elements which are closely linked to the four strategic pillars of the Decent Work Agenda, that is, (i) Core labour standards and fundamental principles and rights at work (ii) Employment creation (iii) Social protection and (iv) Social dialogue and tripartism. The ILO Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalisation 2008 has emphasised that the four strategic objectives of the Decent Work Agenda are "inseparable, interrelated and mutually supportive. The failure to promote any one of them would harm progress towards the others”.[26] Based on the recommendation of the 2008 ILO Declaration to establish appropriate indicators to monitor and evaluate the progress achieved, the ILO adopted a framework of statistical and legal Decent Work Indicators.

The framework indicators cover the ten substantive elements of the Decent Work Agenda. These elements are:[27]

- Employment opportunities

- Adequate earnings and productive work

- Decent working time

- Combining work, family and personal life

- Work that should be abolished (child labour and forced labour)

- Stability and security of work

- Equal opportunity and treatment in employment

- Safe work environment

- Social security

- Social dialogue, employers' and workers' representation

Progress on Target 8.8, requiring protection of labour rights for all workers, including those in precarious employment, can be measured only through the comprehensive Labour Rights Index. Given the labour market havoc wreaked by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate changes in recent years[28], this is the most opportune time to address the protection of all labour rights and measure the progress of member countries. It is time to measure every country's progress on all labour protections, as stipulated in Target 8.8.

The Index is further built on the WageIndicaor Decent Work Checks, which have detailed explanations of de jure provisions on various workplace rights under national labour laws. These country documents are revised on an annual basis.

While many would argue against building another index focusing only on de jure labour market institutions and provisions (namely, due to the existence of large informal sectors in developing countries, non-compliance coupled with the tepid and lacklustre implementation of labour laws), well-drafted and inclusive laws are still a precondition for attaining decent work. Well-drafted laws provide clear and explicit answers to difficult and perplexing questions.

The results and insights from the comparative Labour Rights Index can be used to bring much-needed labour legislation reforms in various countries. Universal labour guarantees or basic labour protections should be available to everyone. This essentially means that all workers, regardless of their contractual arrangement or employment status, should enjoy fundamental workers' rights (freedom of association and right to collective bargaining, non-discrimination, no forced or child labour), an adequate living wage, maximum limits on working hours, safety and health at work, and access to the social protection system. The Index will not only help reform and develop missing legal provisions but will also help in tracing the jurisprudential evolution of legal systems in one of the most impressionable legal spheres.

Progress on Target 8.8, requiring protection of labour rights for all workers, including those in precarious employment, can be measured only through the comprehensive Labour Rights Index. Given the labour market havoc wreaked by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate changes in recent years[28], this is the most opportune time to address the protection of all labour rights and measure the progress of member countries. It is time to measure every country's progress on all labour protections, as stipulated in Target 8.8.

Data Notes

The Wagelndicator Foundation and the Centre for Labour Research have developed the Labour Rights Index, which looks at the status of countries in terms of providing laws related to decent work for the labour force. The data set covers 10 indicators for 145 countries. The Index aims to provide a snapshot of the labour rights present in the legislation of the countries covered.

The following assumptions have been used while constructing the Labour Rights Index. The worker in question

- Is skilled;[29]

- Is at least a minimum wage worker;

- Resides in the economy's most populous province/state/area;

- Is a lawful citizen or a legal immigrant of the economy; [30]

- Is a full-time employee with a permanent contract in a medium-sized enterprise with at least 60 employees;

- Has work experience of one year or more;

- Is assumed to be registered with the relevant social security institution and for a long enough time to accrue various monetary benefits (maternity, sickness, work injury, old age pension, survivors', and invalidity benefit); and

- Is assumed to have been working long enough to access leaves (maternity, paternity, paternal, sick, and annual leave) and various social benefits, including unemployment benefits.

Methodology

The scores for each indicator are obtained by computing the unweighted average of the answers under that indicator and scaling the result to 100. The final scores for the countries are then determined by taking each indicator's average, where 100 is the maximum score to achieve. Where an indicator has four questions, each question/component has a score of 25. Where an indicator has five questions, each question/component has a score of 20. A Labour Rights Index score of 100 would indicate that there are no statutory decent work deficits in the areas covered by the Index.

The subtopics in a Decent Work Check (DWC)[31] have been used to structure 46 questions under the indicators in constructing this Index. However, what differentiates the Labour Rights Index from the Decent Work Checks is that it is more specific, adds newer topics like pregnancy inquiry, comparison between minimum age for employment and compulsory schooling age, and scoring of freedom of association questions is not solely dependent on labour legislation in the country. Forty-six data points are obtained across 10 indicators, each containing four to five binary questions. Each indicator represents an aspect of work which is considered important for achieving decent work.[32]

The scores for each indicator are obtained by computing the unweighted average of the answers under that indicator and scaling the result to 100. The final scores for the countries are then determined by taking each indicator's average, where 100 is the maximum score to achieve. Where an indicator has four questions, each question/component has a score of 25. Where an indicator has five questions, each question/component has a score of 20. A Labour Rights Index score of 100 would indicate that there are no statutory decent work deficits in the areas covered by the Index.

Conceptual Framework

The Index consists of ten elements disaggregated into 46 components. These indicators and their components are presented below. Detailed description for each component can be found in the section on Indicators for Decent Work.

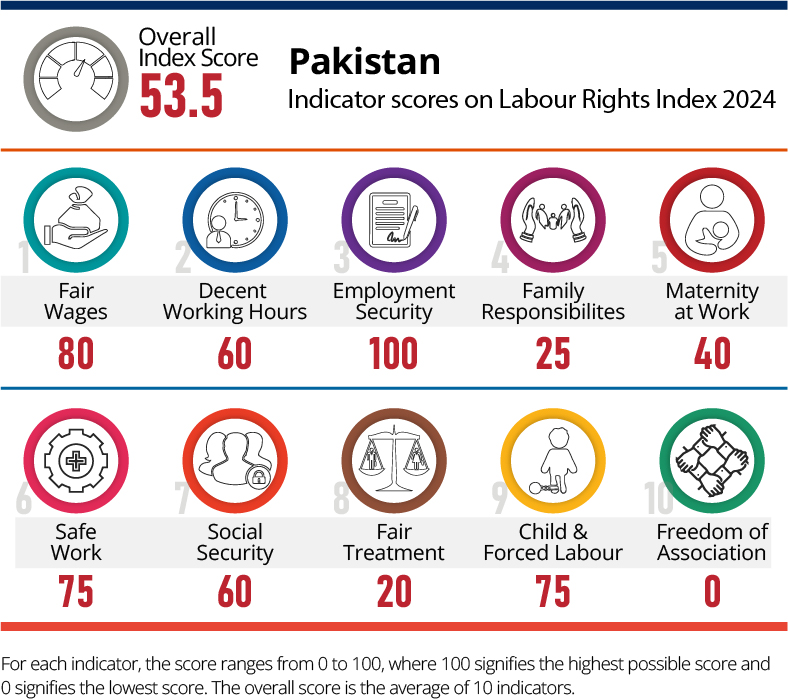

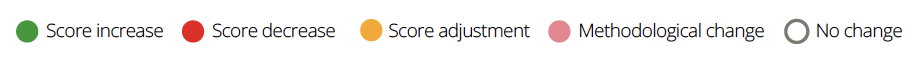

To illustrate the scoring process in the Index, Pakistan, for example, receives a score of 75 under the indicator of Child and Forced Labour. This signifies that the country generally has legal protections in place for children and young persons participating in the labour market, however the legislation allows employment of children before completion of compulsory schooling. Under the indicator of Family Responsibilities, Pakistan scores 25 since the legislation does not guarantee parental leave, flexible work arrangements for workers with family responsibilities, and paid nursing breaks.

Scoring along these lines for a country, the overall score of Pakistan is determined by taking the unweighted average of the scores for all 10 indicators on a 0-100 scale, where 0 represents the worst regulatory performance and 100 the best regulatory performance in the labour market. The overall score for Pakistan is 53.5. For a comparison with other countries, please refer to the overall scores table at the start of this report.

The labour legislation of the 145 countries, applicable on 1 January 2024, is the source of information used to answer questions in the Labour Rights Index. Strengths and limitations exist with this approach. While the Labour Rights Index has been designed to be an easily replicable tool to benchmark countries, there are certain advantages and limitations. To ensure comparability of data across 145 economies, specific assumptions have been made. The indicators in the Index are based on standardised assumptions to make the laws comparable across countries. For instance, an assumption used for this Index is that the worker in question who is affected by the labour laws has experience of one year or more at a workplace, as questions on annual leave and severance pay can only apply to this kind of worker. Hence, workers with temporary contracts of a duration of less than one year may not have access to such rights.

Another assumption underlying the Index is that the focus is on the labour legislation, which applies to the most populous province/state/area of a country.

This allows the Index to give a more accurate depiction of a country's labour rights as the labour laws affect most of its population, even though the legislation affecting workers in areas with lower populations may be different.

Furthermore, the Index is also based on labour legislation which applies to the formal economy in the private sector. Despite more than 60 per cent of the global workforce in need of transitioning from informal to the formal economy[33] focusing on the labour laws affecting the formal sector retains attention on the sector since the labour laws in the formal economy are more applicable and that is the ultimate goal. ILO Recommendation 204 also recommends gradual transition from the informal to the formal economy through the enactment of necessary legislation and reduction of barriers to transition. Focusing on the formal economy and its applicable legislation also indicates the kind of rights that will be available to the informal economy workers on successful transition to the formal economy.

Other than statutes, the Labour Rights Index also considers general or inter-professional collective agreements applicable at the national level. For countries where minimum wages are determined through collective bargaining, sectoral agreements (for major economic sectors) can also be considered.

Strengths and Limitations of the Labour Rights Index

| Feature | Strength | Limitation |

| Standardised assumptions | Makes labour legislation comparable across countries and methodology uncomplicated | Limits legislation under review |

| Focus on workers having one year or more at a workplace | Allows maximum coverage of labour rights | Does not consider the rights of casual and temporary workers. Non-standard workers may not have access to some of the workplace rights and components under the Labour Rights Index |

| Coverage of most populous province/state/area | Makes labour legislation comparable across countries where different areas have different labour laws for their populations; Gives a more accurate picture of a country’s labour rights | Can decrease representativeness of labour rights where differences in laws across areas exist |

| Focus on the formal economy | Retains attention on the formal sector where labour laws are more applicable | Does not cover the rights of the workforce in the informal economy, which could have a substantial part of the labour force in some countries |

| Use of codified national labour legislation only | Allows actionable indicators since the law can be changed by policymakers | Where lack of implementation of labour legislation, making changes solely in the law will not gain the desired outcome; Does not consider socio-cultural norms |

Moreover, this report acknowledges the presence of gaps between legislation and its practice. For instance, gaps could stem from the lack of implementation of laws because of poor enforcement, weak design, or limited capacity. Still, observing differences in legislation helps give a clearer understanding of where labour rights may be limited in practice. This study also recognises the presence of social, economic and cultural factors affecting the practice of legal rights. For example, women may not be working at night, although legally allowed, as social and cultural norms could restrain such options. Or a lack of safe transport may limit women's employment during night hours. Poverty-stricken areas may have children under the minimum working age being employed for long hours and not in light work. Workers may be doing overtime exceeding the weekly hour limit because the culture at their organisations may view such workers as harder working and thus more deserving of a reward. The Labour Rights Index 2024 acknowledges the restraints of its standardised assumptions and focuses on codified law. Even if these assumptions do not cover all the labour force in the country, they ensure the comparability of data.

Unlike other indices, the Labour Rights Index does not consider ratification of international conventions in its scoring or rating system since mere ratification is not a good indicator of actual implementation of international labour standards.

It uses the standards prescribed in these Conventions (e.g., 14 weeks of maternity leave or the minimum age for hazardous work as 18 years) and scores countries on that basis. All the 10 indicators and 46 evaluation criteria of the Labour Rights Index are grounded in substantive elements of the Decent Work Agenda. The legal basis for all components (regulatory standards) emanates from the UN or ILO Conventions. Table explains in detail these legal sources.

In summary, the Labour Rights Index methodology has various useful features. The methodology:

- Is transparent and based on facts taken directly from codified laws.

- Uses standardised assumptions for data collection, thereby making logical comparisons across countries.

- Allows data to identify the labour rights and their presence (or lack of) in the legislation of 145 countries.

International Regulatory Standards and Labour Rights Index

| Indicators and Components | Source of the Regulatory Standard | |

| 1. Fair Wages | ||

| 1 | Minimum wage (statutory or negotiated) | Article 23 (3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 3 of Minimum Wage Fixing Convention 1970 (No. 131); Article 7 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social & Cultural Rights (Fair Wage clauses) |

| 2 | Regular wage | Article 12 (1) of Protection of Wages Convention 1949 (No. 95); Article 11 (6) and 12 of Social Policy (Basic Aims and Standards) Convention 1962 (No. 117) |

| 3 | Overtime premium (≥125%) | Article 6 of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 7 of the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1930 (No. 30) |

| 4 | Weekly rest work compensation (time- off) | Article 5 of the Weekly Rest (Industry) Convention, 1921 (No. 14); Article 8 (3) of the Weekly Rest (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1957 (No. 106)[1] |

| 5 | Night work premium | Article 8 of Night Work Convention, 1990 (No. 171) |

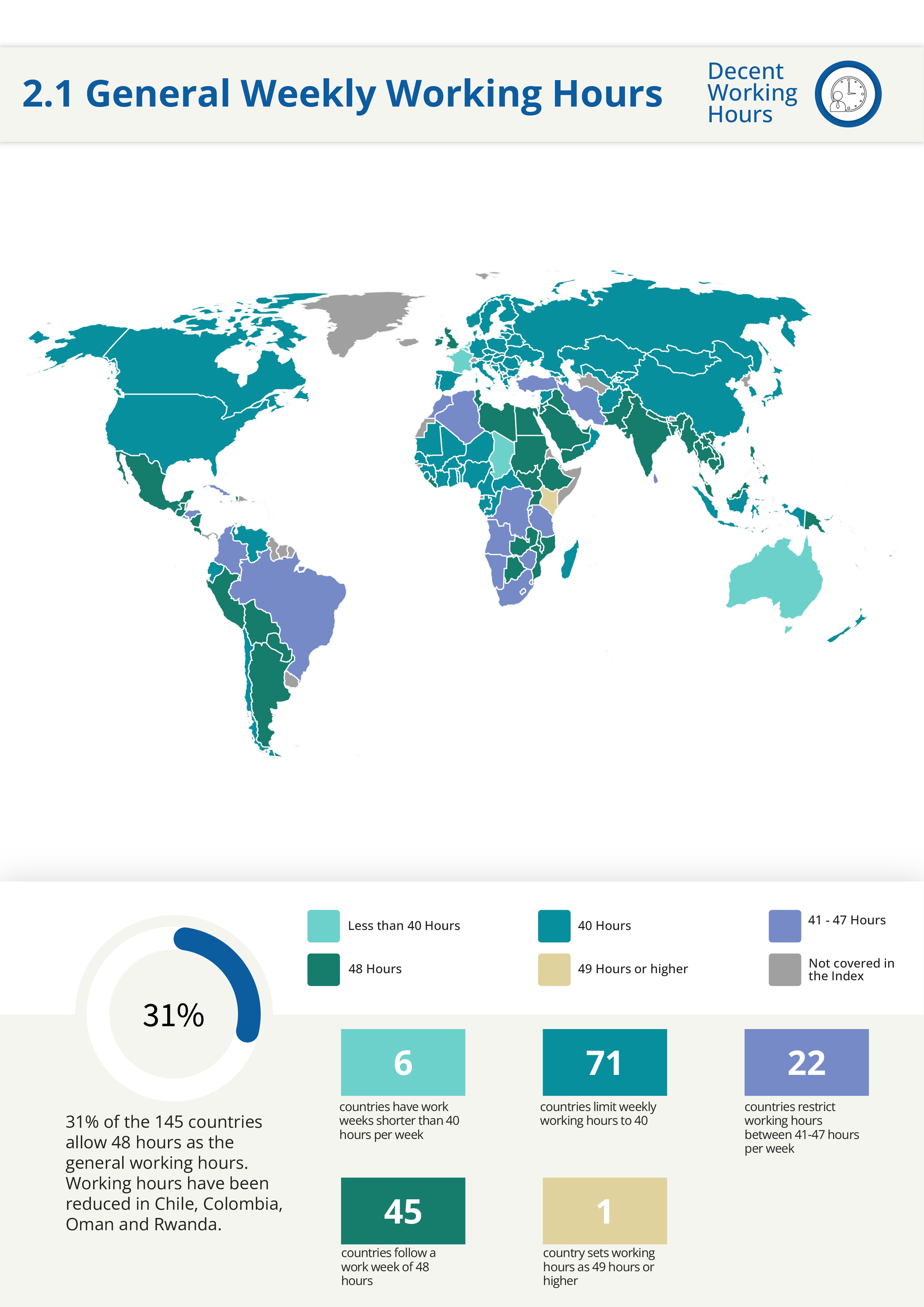

| 2. Decent Working Hours | ||

| 6 | General working hours (≤48 hours per week) | Article 2 of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 3 of the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1930 (No. 30); Article 1 of the Forty-Hour Week Convention, 1935 (No. 47) |

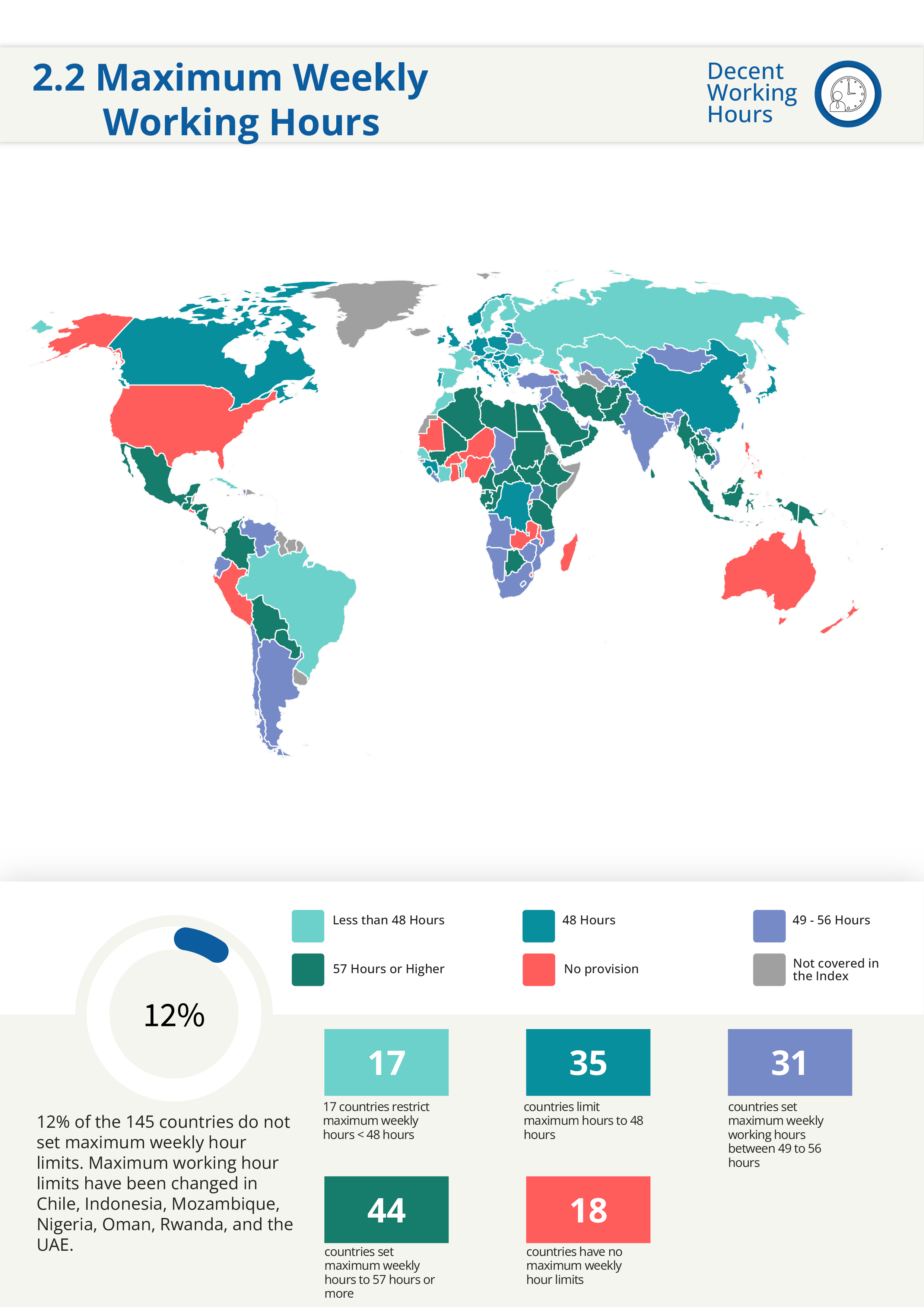

| 7 | Maximum working hours (≤56 hours per week) | Para 17 of the Reduction of Hours of Work Recommendation, 1962 (No. 116); Article 6 (2) of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 7 (3) of the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1930 (No. 30) |

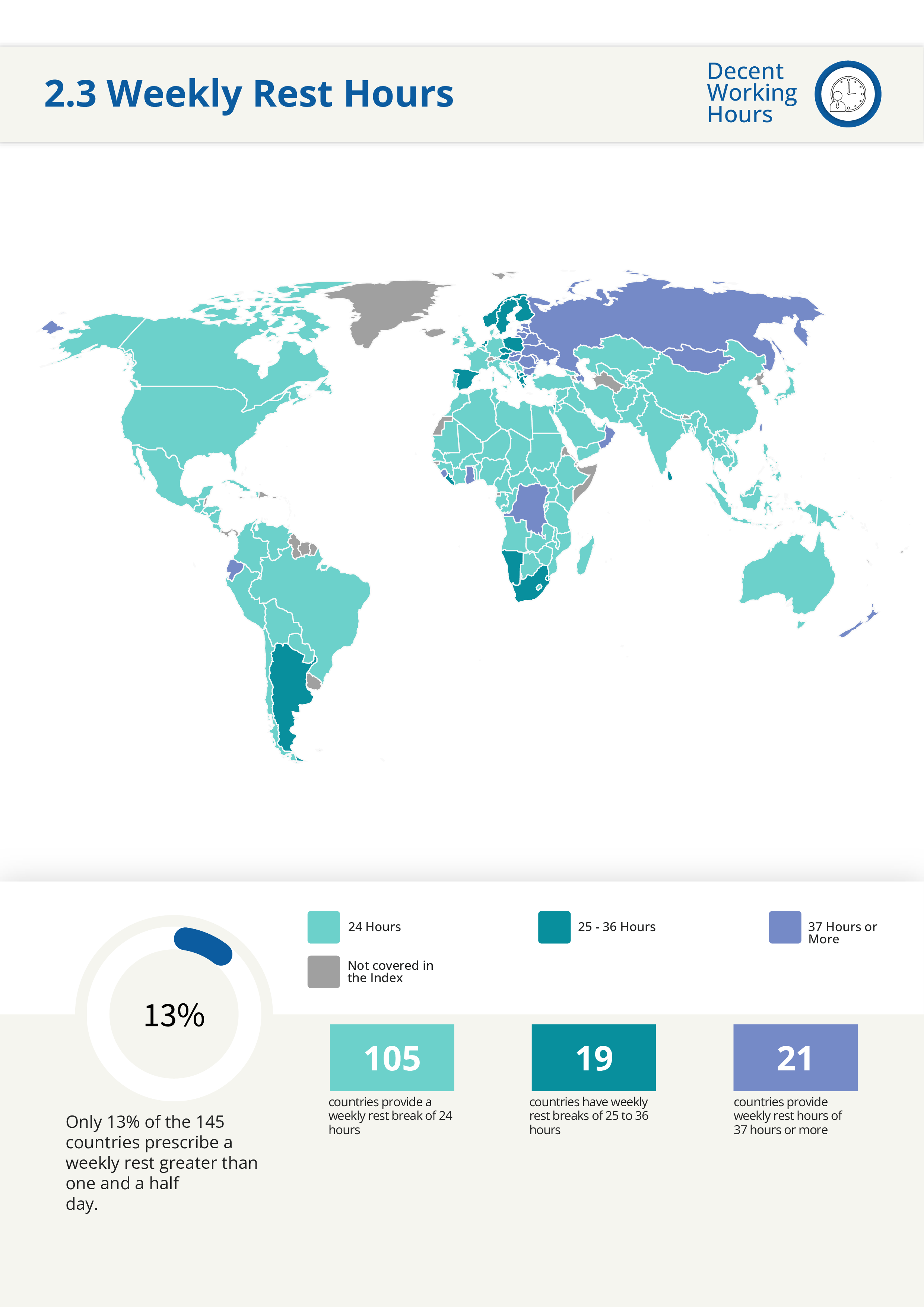

| 8 | Weekly rest (≥24 hours) | Articles 3-6 of Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919 (No. 1); Article 2 of Weekly Rest (Industry) Convention 1921; Article 6 of Weekly Rest (Commerce and Offices) Convention 1957 |

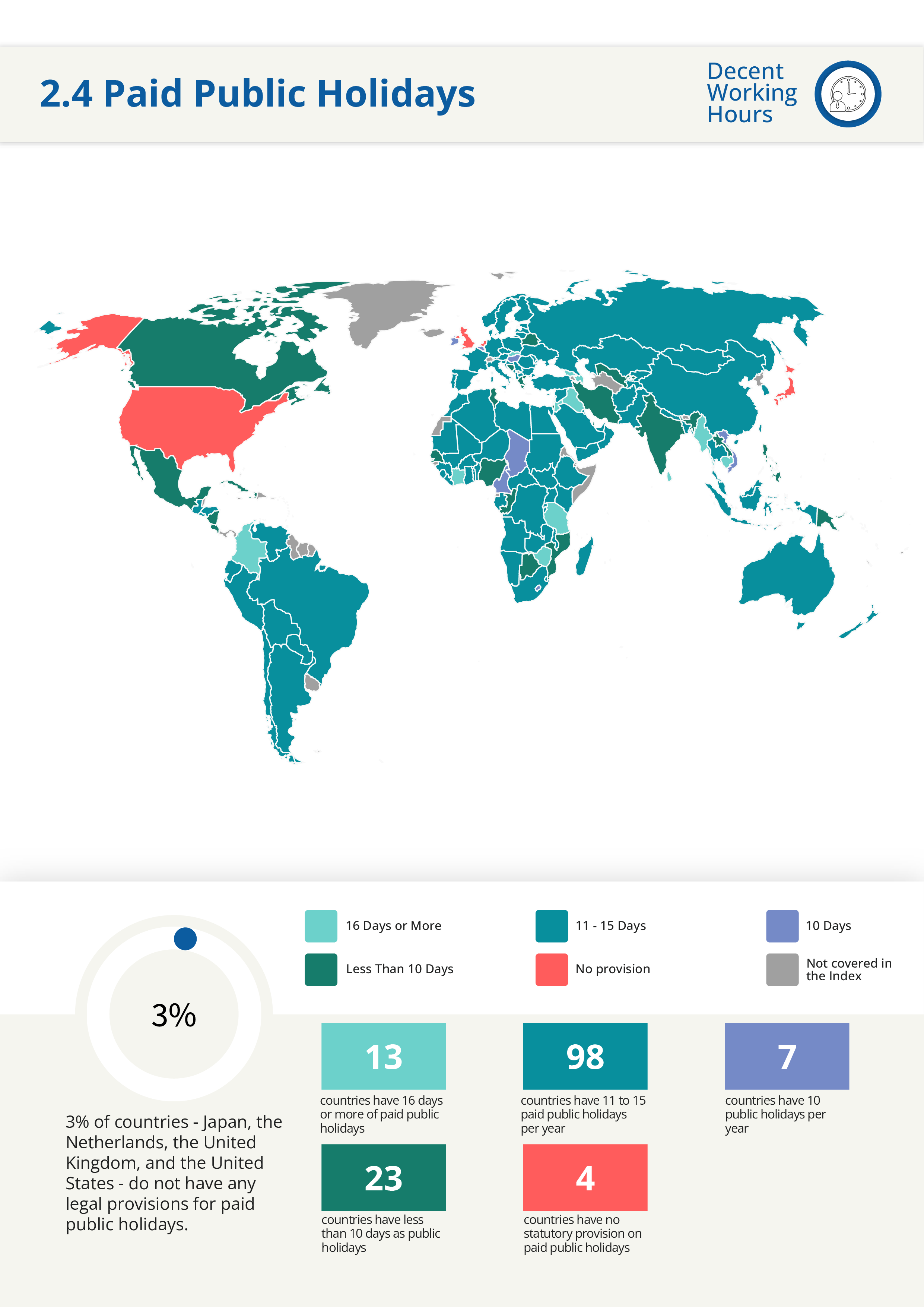

| 9 | Paid public holidays | Article 5 of Working Conditions (Hotels and Restaurants) Convention 1991 (No. 172); Article 6 (1) of Holidays with Pay Convention (Revised) 1970 (No. 132); Article 7 (c) of the Part-Time Work Convention, 1994 (No. 175) |

| 10 | Annual leave (≥3 working weeks) | Article 3 of Holidays with Pay Convention (Revised) 1970 (No. 132) |

| 3. Employment Security | ||

| 11 | Written employment contract | Articles 7-8 of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189); Part II (5) of the Private Employment Agencies Recommendation, 1997 (No. 188) |

| 12 | Fixed term contract (≤5 years) | Article 2 (3) of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158); Article 3 (2) of the Termination of Employment Recommendation, 1982 (No. 166) |

| 13 | Probation period (≤3 months) | Article 2 (b) of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158) |

| 14 | Termination notice period (1 month) | Article 11 of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158) |

| 15 | Severance pay (≥14 days per year of service) | Article 12 of the Termination of Employment Convention 1982 (No. 158) |

| 4. Family Responsibilities | ||

| 16 | Parental leave | Article 1 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156); Paragraph 22 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Recommendation, 1981 (No. 165); Paragraph 10 of the Maternity Protection Recommendation, 2000 (No. 191) |

| 17 | Paternity leave (≥1 week) | 2009 ILC Resolution Concerning Gender Equality at the Heart of Decent Work |

| 18 | Flexible working arrangements | Article 1 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156); Paragraph 18 of the Workers with Family Responsibilities Recommendation, 1981 (No. 165); Article 9 (2) of the Part-Time Work Convention, 1994 (No. 175) |

| 19 | Nursing breaks | Article 10 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 5. Maternity at Work | ||

| 20 | Prohibition on inquiring about pregnancy | Article 9 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 21 | Maternity leave (≥14 weeks) | Article 4 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); Article 11 (2) of UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) |

| 22 | Cash maternity benefits (≥66.67% of former wage) | Article 6 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 23 | Source of maternity benefits (social insurance or state financing) | Article 6(8) of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

| 24 | Protection from dismissals (pregnancy/maternity) | Article 8 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); Article 11 (2) (a) of UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) |

| 6. Safe Work | ||

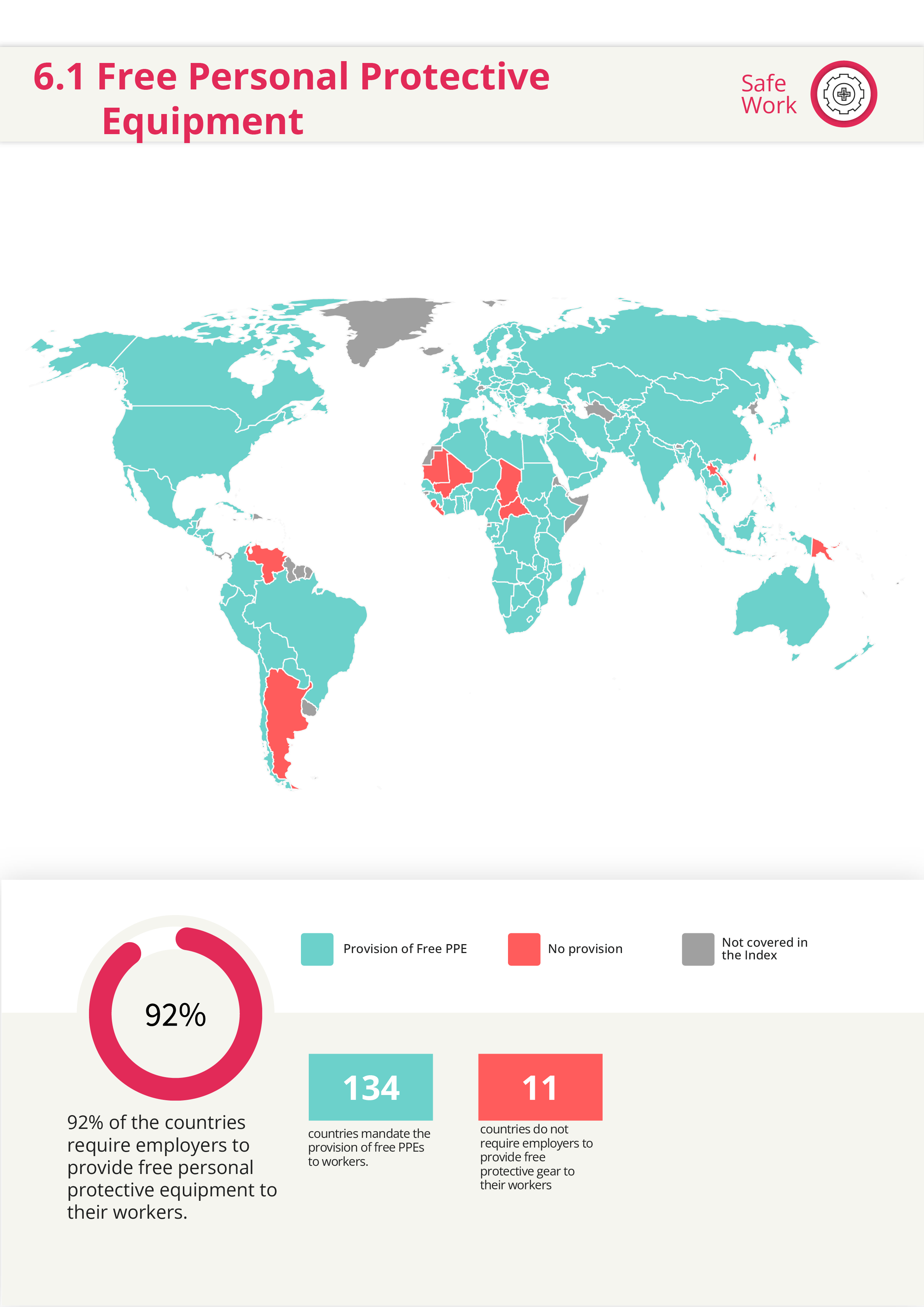

| 25 | Personal protective equipment (free of cost) | Article 16 and 21 of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) |

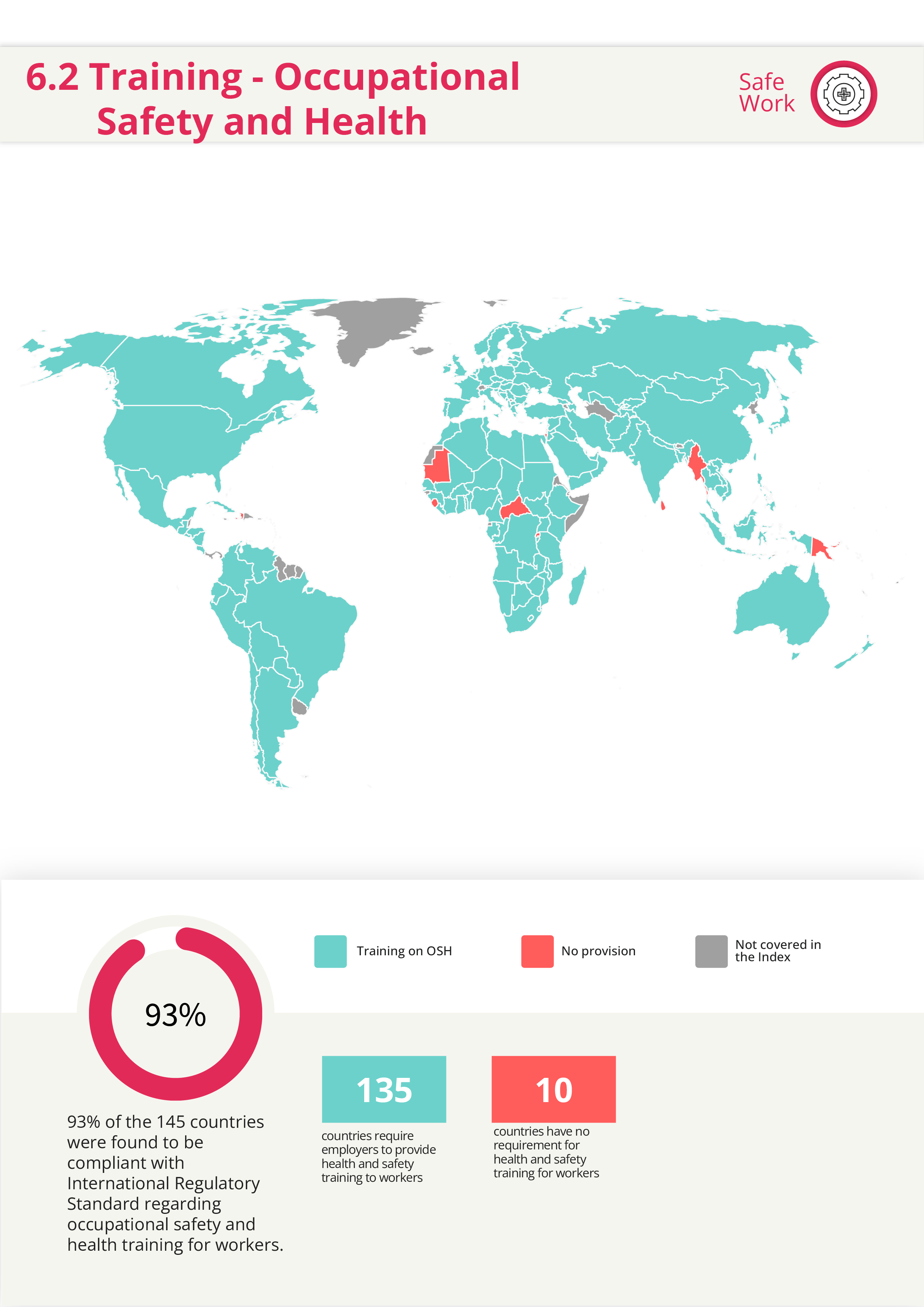

| 26 | Training on health and safety | Article 19 (d) of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) |

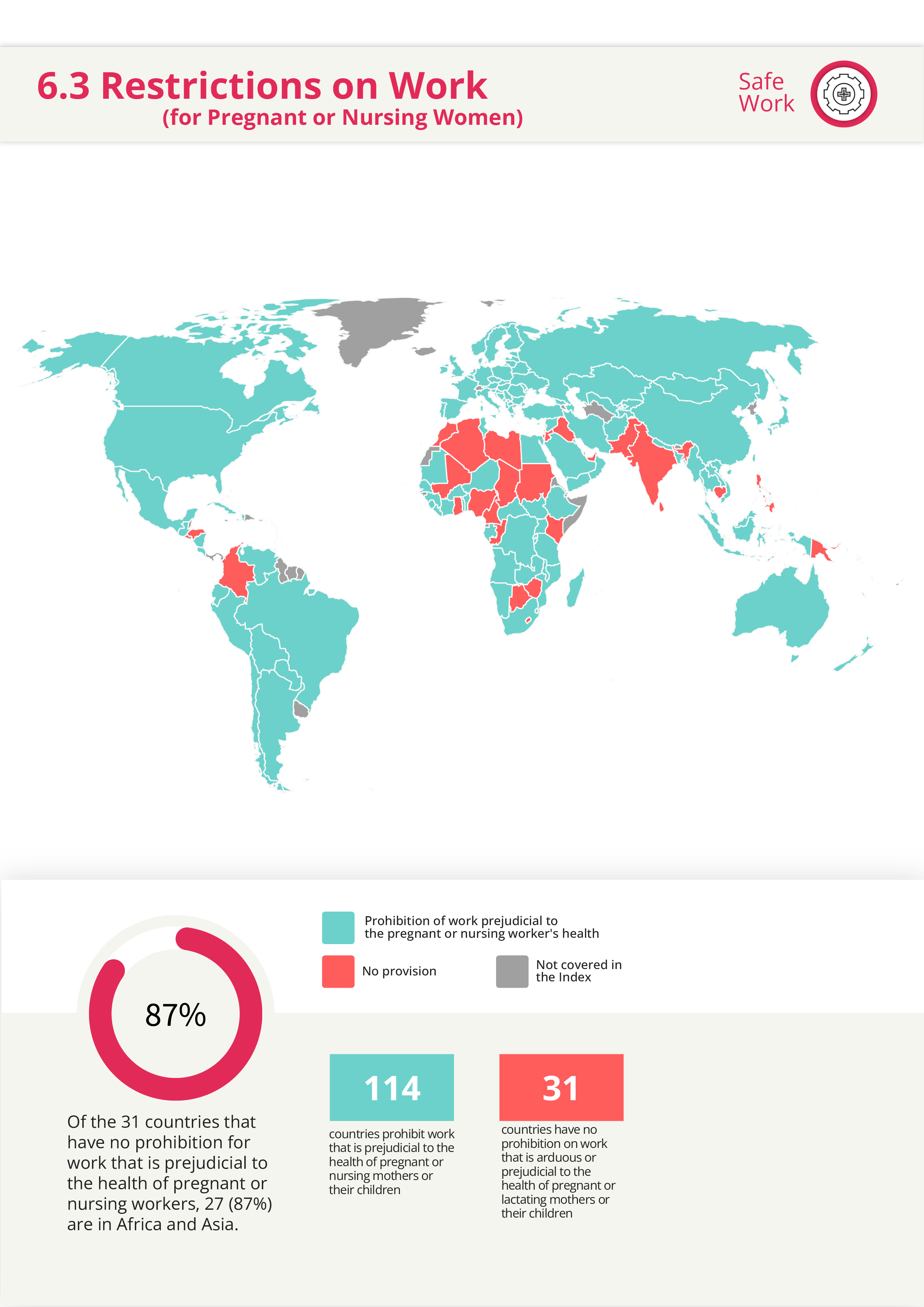

| 27 | Restriction on work (prejudicial to health of mother or child) | Article 3 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183) |

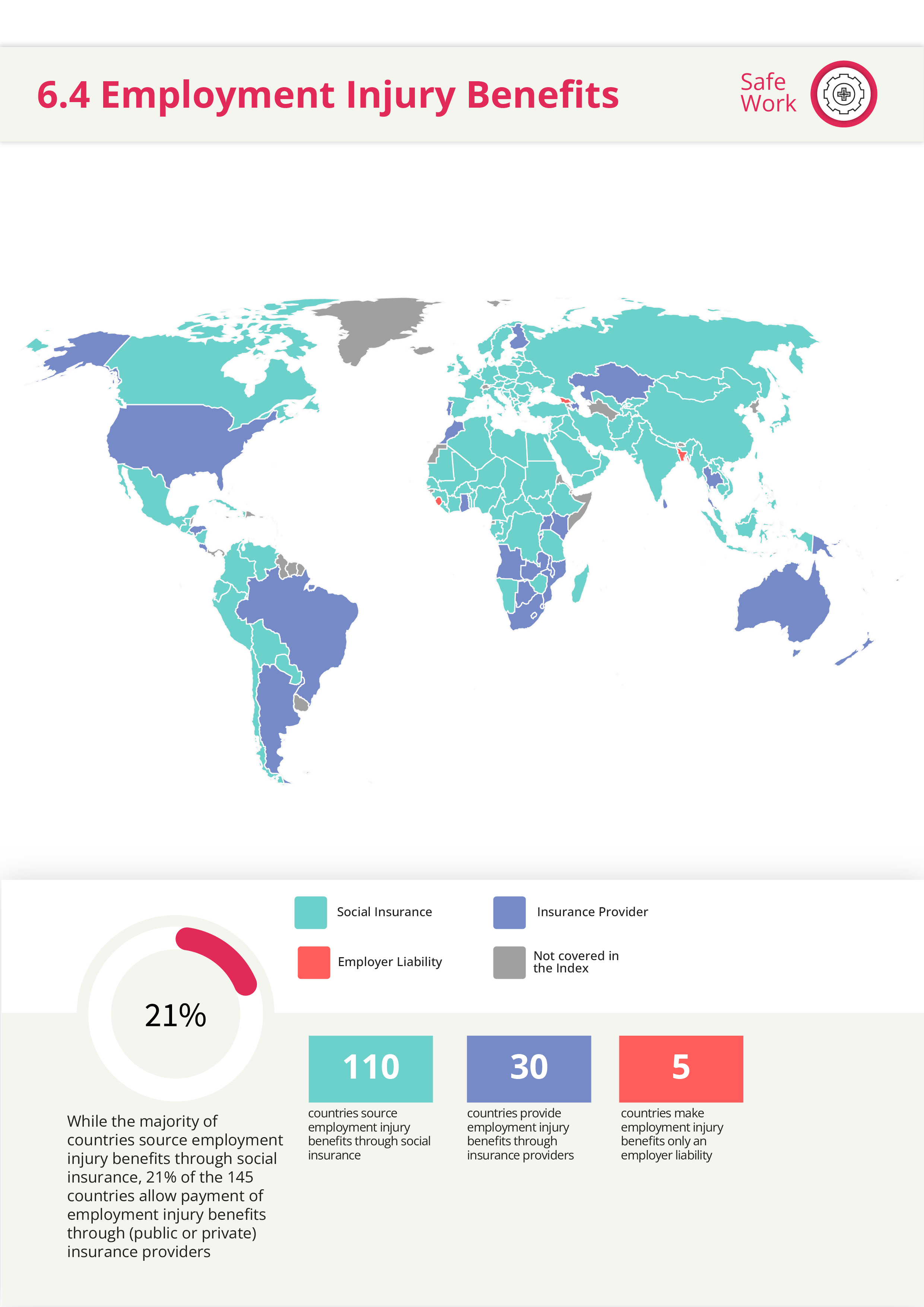

| 28 | Employment injury benefits | Part VI of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 7. Social Security | ||

| 29 | Old age benefits | Part V of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 30 | Survivors’ benefits | Part X of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 31 | Unemployment benefits | Part IV of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 32 | Sickness benefits (≥ 6 months) | Part III of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 33 | Invalidity benefits | Part IX of the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102) |

| 8. Fair Treatment | ||

| 34 | Prohibition of employment discrimination | Article 2 of the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111); Articles 8 and 9 of the Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183); Article 4 of the Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment (Disabled Persons) Convention, 1983 (No. 159); Article 1 of the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98); Article 5 and 27 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| 35 | Equal remuneration for work of equal value | Article 2 of the Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100) |

| 36 | Prohibition of sexual harassment | Article 7 of the Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (No. 190) |

| 37 | Absence of restrictions on women’s employment | Article 2 of the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111) |

| 38 | Basic labour protections for gig workers | Global Commission on the Future of Work 2019[2]; Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (MNE Declaration), 2017 |

| 9. Child and Forced Labour | ||

| 39 | Prohibition on child labour (<15 years) | Article 2 of Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138); Article 32 (2) of the Convention on Rights of Child |

| 40 | Age (employment entry ≥ compulsory schooling) | Article 2(3) of Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138) |

| 41 | Prohibition on hazardous work for under 18 | Article 3 of Minimum Age Convention 1973 (No. 138); Article 32 (1) of the Convention on Rights of Child |

| 42 | Prohibition on forced labour | Article 2 of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29); Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, 1930; Article 8 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

| 10. Freedom of Association | ||

| 43 | Right to unionise | Article 2 of the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87) |

| 44 | Right to collective bargaining | Article 4 of the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98), Article 2 of the Collective Bargaining Convention, 1981 (No. 154) |

| 45 | Right to strike | Para 751, Compilation of Decisions of the Committee on Freedom of Association, 2018 |

| 46 | Sanctions against striking workers | Article 1 of the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98) |

Data Sources and Collection

While the Index is essentially based on Decent Work Checks, the 2024 Index has 10 new countries for which Decent Work Checks are yet to be developed. For all countries, labour legislation, including various decrees, amendments and collective agreements, was revisited to score each component and provide a direct legal basis. The legal basis has been provided in individual country profiles. The cut-off date for all data collection is 1 January 2024. Any legislation or change in the law that occurs after said date, where the effective date is set later than 1 January 2022, or where the effective date is not yet precisely known, is not reflected in the Index. However, the situation in individual countries might have shifted.

The Scoring System

We use a dichotomous scoring system for the 46 indicators (1 for a yes and 0 for a no). Non-binary scores (such as a scale of 1 to 5) introduce difficulties in defining meaningful and comparable standards or guidelines for each score. This can lead to arbitrary, erroneous and incomparable scores. For example, a 2 for one country may be a 3 for another, and so on. Alternatively, an expert may find a country- specific indicator that differs from another country. This violates a fundamental principle of measurement known as reliability — the degree to which a measurement procedure produces accurate measurements every time, regardless of who performed it.

Weights

The Labour Rights Index does not use weights. Each indicator features either four or five underlying components framed as questions. Every component contributes equally to the indicator, and every indicator contributes equally to the overall score. The overall score (from 0-100) is calculated from a simple unweighted average of scores from 10 indicators.

As pointed out at the outset, the indicators and components of the Labour Rights Index cover the employment lifecycle of a person. Consider the example of annual leave and sick leave. While annual leave is accessed by a greater percentage of workers every year compared with sick leave, giving them weights (whether equal or unequal) would be arbitrary and would not serve the purpose.

Similarly, consider the example of child labour and forced labour questions. While the majority of workers may not have to experience these menaces, it is a harsh reality for many, at least in developing countries. Giving weights would mean prioritising one component over the other.

Countries at different stages of development may also have different legal provisions. For example, as is evident throughout the study, work-life balance and gender equality related legislation is also linked with economic development. With certain exceptions, most high-income countries have instituted provisions on paternity leave and parental leave.

If these components are given higher weightage than the other, developing countries' scores will be comparatively much lower.

Greater weightage to certain areas of labour law can create an inherent bias and also lead to the agents' skewed efforts to initiate reforms in areas with higher weights. Countries will inherently target laws with greater weightage.

If giving weights were an option, fundamental principles and rights at work would be given higher weights. These are freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour; the effective abolition of child labour; the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation, and a safe and healthy working environment[34].

Even before the amendment of the 1998 Declaration in 2022, ILO had started giving importance to other workplace rights. The 2019 Declaration notes that "all workers should enjoy adequate protection following the Decent Work Agenda, taking into account:

- Respect for their fundamental rights;

- An adequate minimum wage, statutory or negotiated;

- Maximum limits on working time; and

- Safety and health at work "

Similarly, social protection, or social security (both terms are used interchangeably), is enshrined as such in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966). ILO Recommendation 202 suggests that countries should establish and maintain national social protection floors as a nationally defined set of basic social security guarantees that secure protection to prevent or alleviate poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion.

Hence, instead of preferring one component or indicator over the other, the Labour Rights Index has been developed without assigning weights.

Ranking

The Labour Rights Index does not "rank" countries.

The ordinal ranking method (for example, "first", "second", and "third") is problematic as it leads to the naming and shaming of countries at the bottom of the list. Moreover, as argued by the World Bank's Doing Business Report in 2016, ranking may encourage the agents (countries being ranked) to "game the system”[35] There is a risk that the agents may divert a disproportionate amount of resources and efforts to the areas which are measured/scored while leaving aside areas which are equally important but not scored. To deal with this issue, the Labour Rights Index does not use ordinal ranking, although it covers the whole gamut of labour rights.

The Index does not aim at producing a single number in the form of ranking. Rather it gives a run down on the local labour legislation, supported by detailed Decent Work Checks, updated annually.

The Index does not aim at producing a single number in the form of ranking. Rather it gives a run down on the local labour legislation, supported by detailed Decent Work Checks, updated annually.

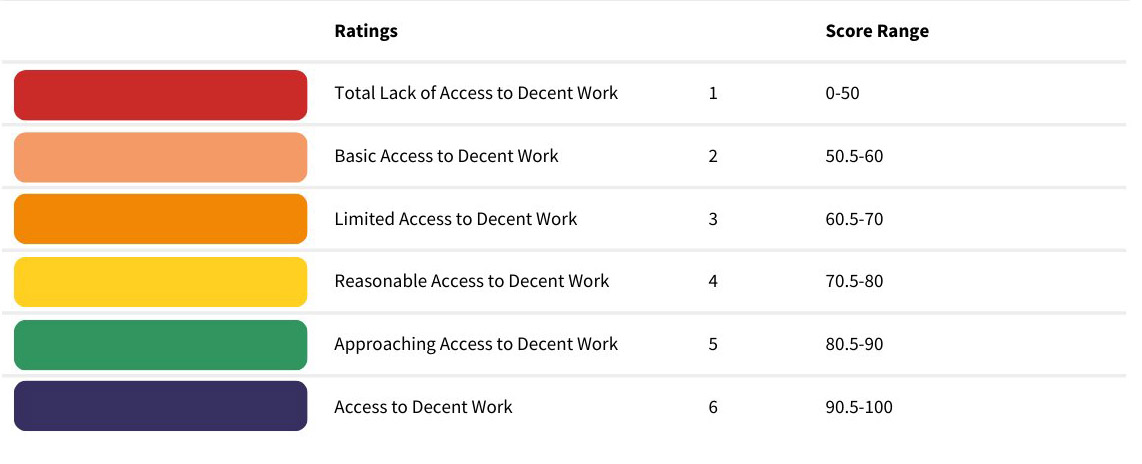

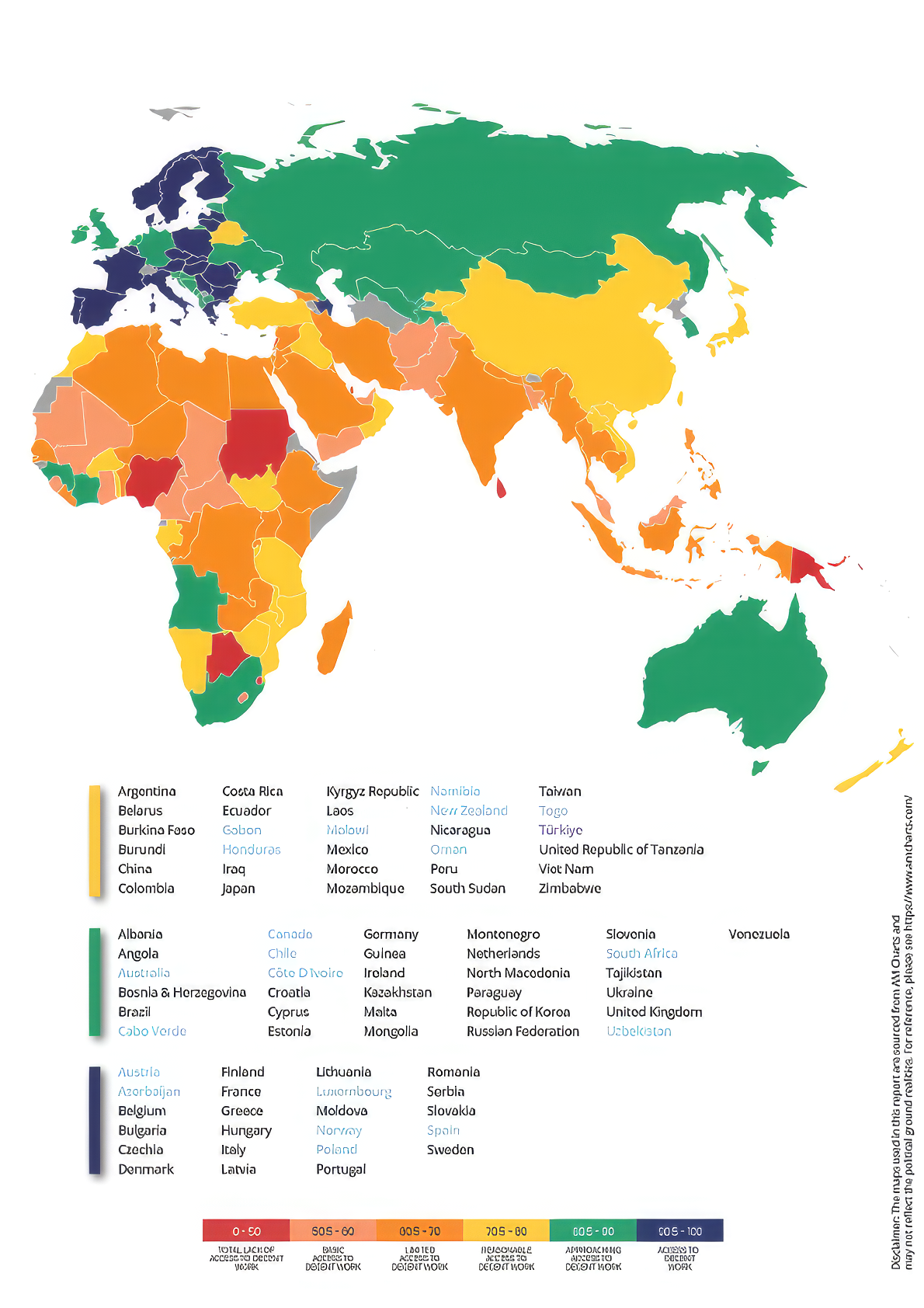

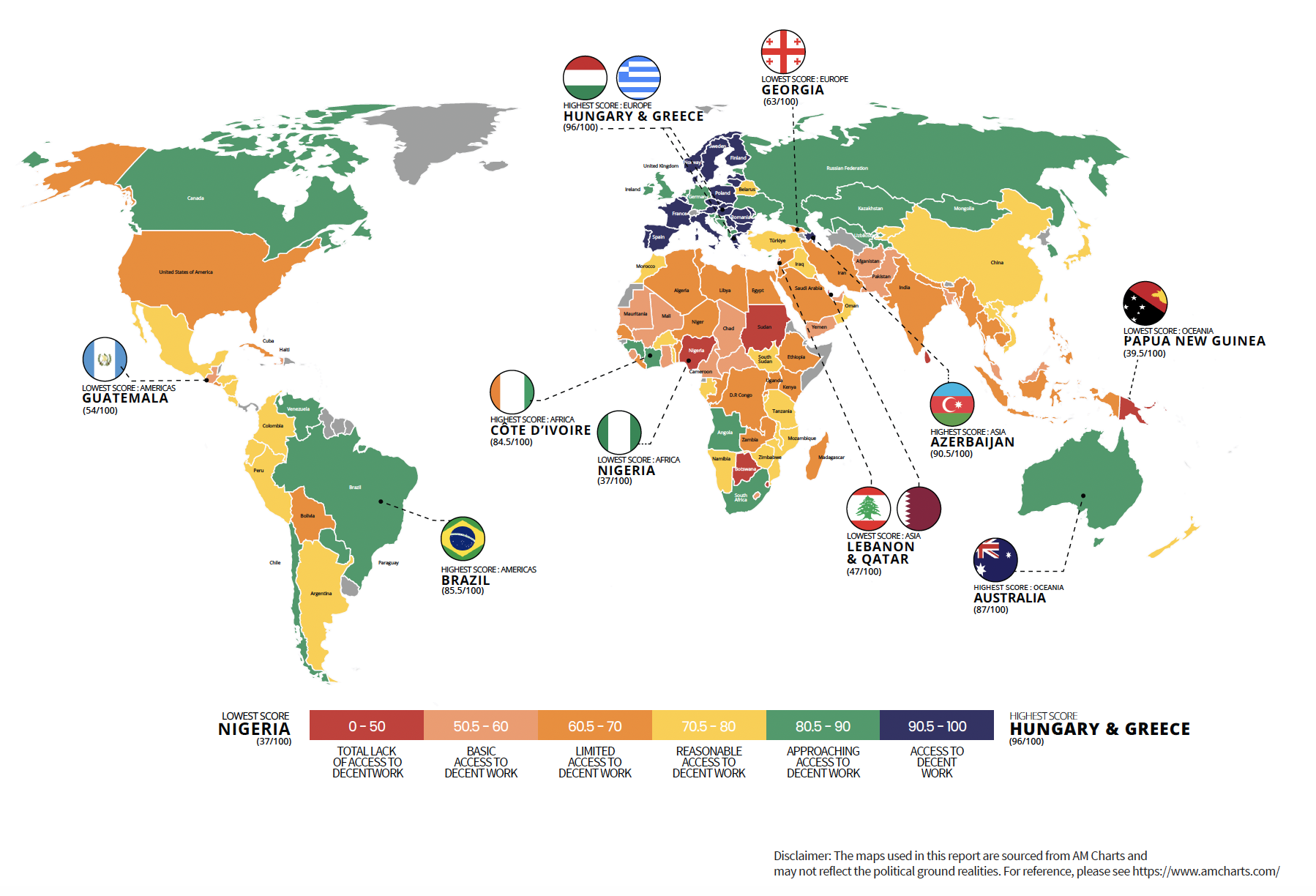

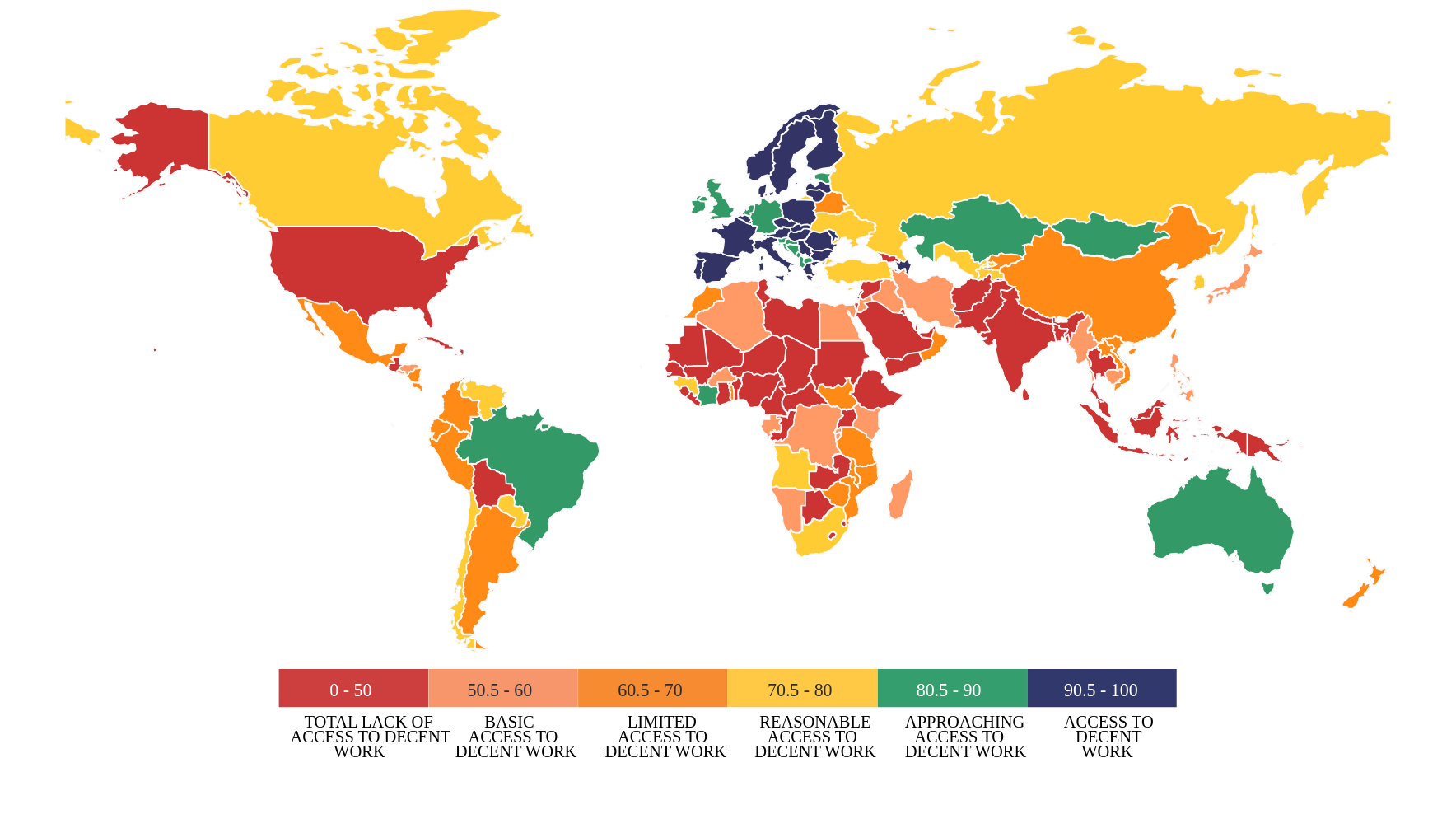

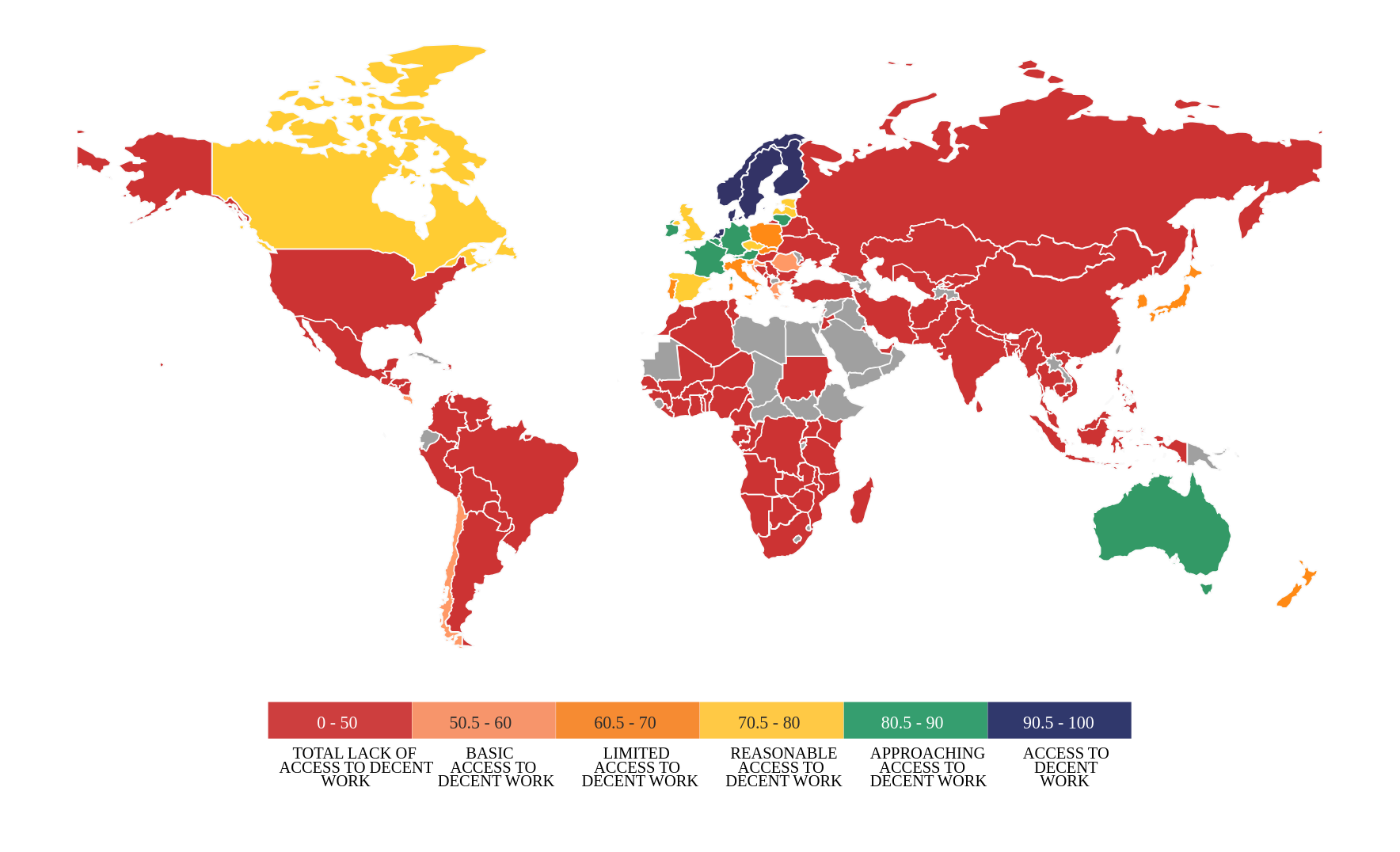

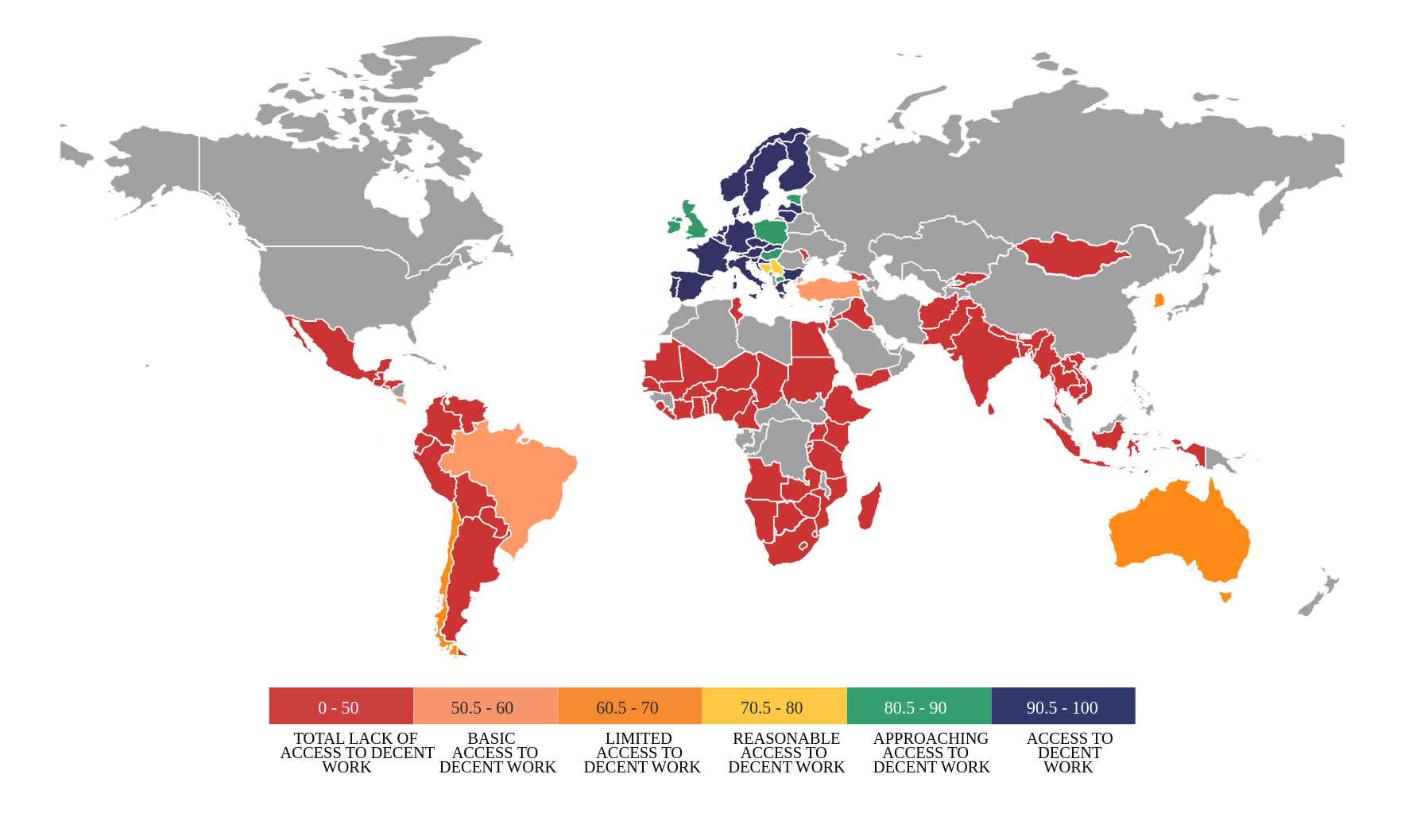

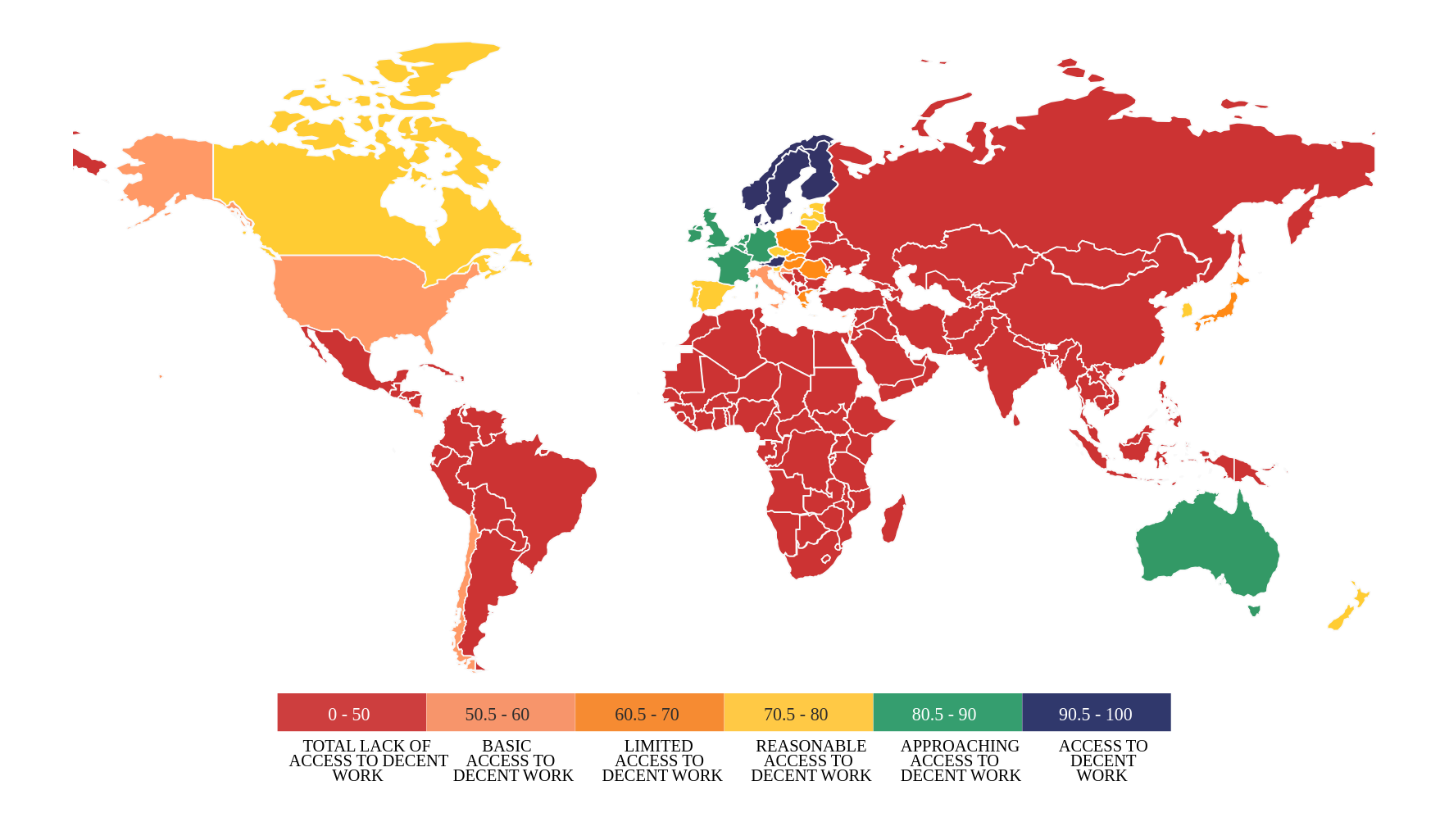

The Labour Rights Index, however, does place 145 countries into six categories and rates these from "Access to Decent Work" to "Total Lack of Access to Decent Work. [36]

How to Read the Country Profiles

The Country Profiles section shows a two-page profile for each of the 145 countries covered in the Labour Rights Index 2024. The country profiles are informative about the major aspects of labour legislation in an economy.

Performance Overview

In this section, the performance of a country in the Labour Rights Index is illustrated. On the top right of the page, the overall average score (out of 100) and rating (out of six categories) give a snapshot of a country's standing in the Labour Rights Index. The top right of the page also shows the overall score in 2020 and 2022, along with region and income group information.

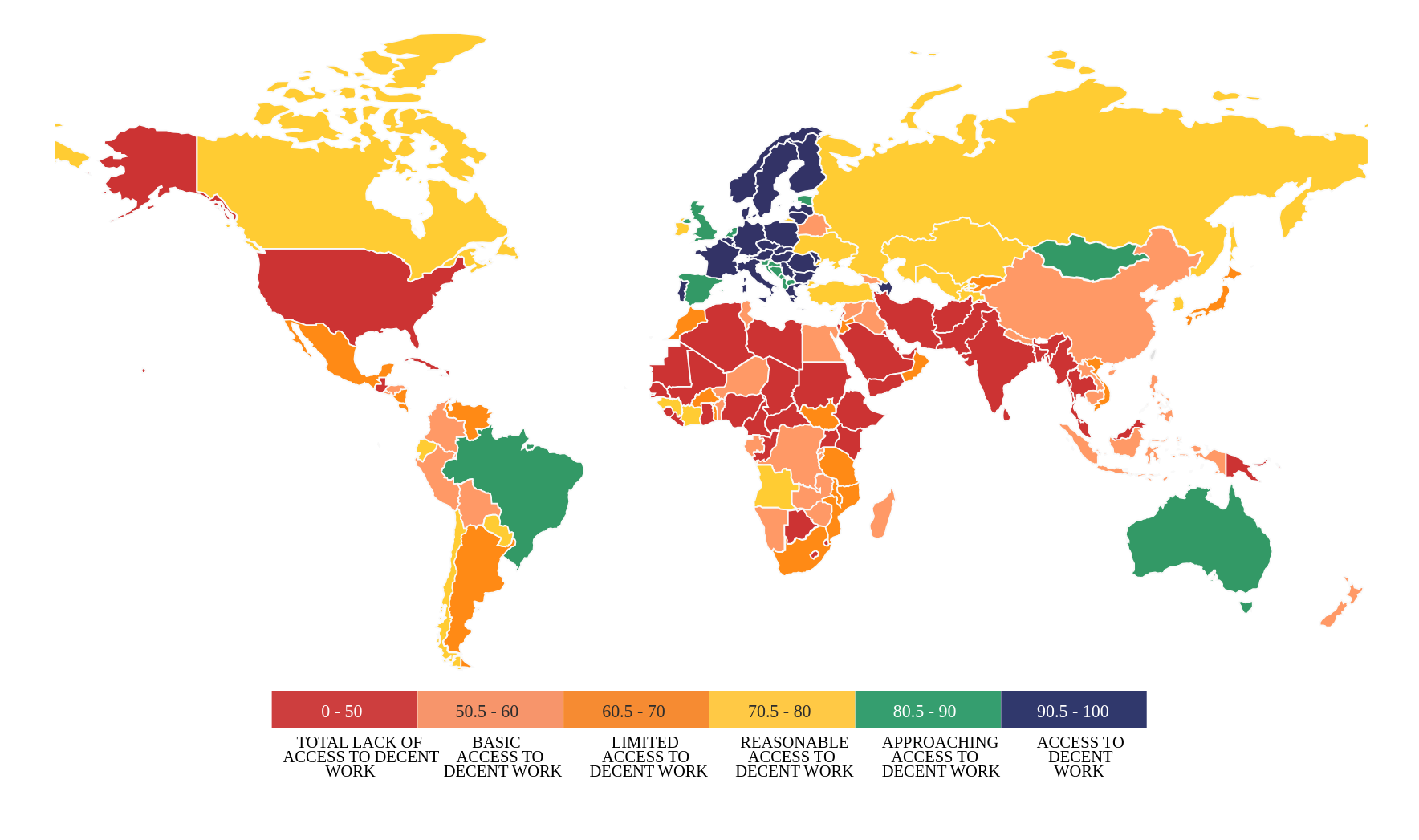

The overall scores benchmark countries with respect to regulatory best practices, as identified in the relevant ILO Conventions, thereby indicating the proximity to the regulatory standard on each component. Each country is allocated ratings according to its overall score. The ratings follow a certain coding; [90.5-100] Access to Decent Work (Blue), [80.5- 90] Approaching Access Decent Work (Green), [70.5-80] Reasonable Access to Decent Work (Yellow), [60.5- 70] Limited Access to Decent Work (Orange), [50.5- 60] Basic Access to Decent Work (Peach), [0-50] Total Lack of Access to Decent Work (Red).

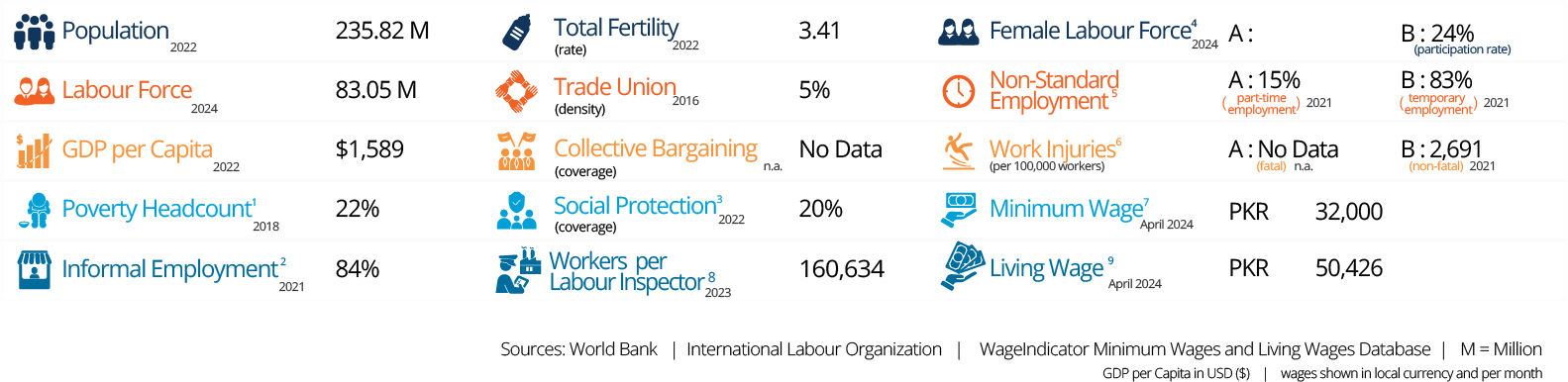

The Contextual Indicators of the country provide a picture of the economy and its labour force at a glance. These facts include Population, Labour Force, GDP per Capita, Poverty Headcount, Informal Employment, Total Fertility rate, Trade Union Density, Collective Bargaining Coverage, Social Protection Coverage, Labour Income Share, Female Labour Force (absolute number and participation rate), Non-Standard Employment (Part-Time Employment-A and Temporary Employment-B), Work Injuries (Fatal and Non-Fatal), Minimum Wage, and number of Workers per Labour Inspector. The contextual indicators have been sourced from International Labour Organization, World Bank data, and the Wagelndicator's own Minimum Wages Database.The country scores on the Labour Rights Index must be interpreted with caution, considering also the above referred contextual indicators.

The first page also introduces the Index and gives information about the average regional score and the highest scoring country in the region.

The overall score and each of the indicators are shown on the first page. For each indicator, the score ranges from 0 to 100, where 100 signifies the highest possible score and 0 signifies the lowest score. The overall score is the average score of 10 indicators. To read about the scoring methodology, refer to the chapter on Indicators for Decent Work.

The next three pages of the country profile shows the decent work indicators of the Labour Rights Index and the answer for each component, along with its legal basis. It is a step toward ensuring greater transparency in the scoring of the countries. The last column shows the trend over the previous two years (2022 to 2024); if the score increased due to a positive reform, it decreased due to a legislative reform or if the score was adjusted to increased availability and access to more legal information about the country. A total of 46 components are shown under the 10 indicators for each of the 135 countries in the Labour Rights Index.

The last page of the Index has necessary end notes and colour legends to explain the changes in country scores.

Description of the Ratings

1 - Total Lack of Access to Decent Work

Decent work deficits are rife in countries with a rating of 1 (Total Lack of Access to Decent Work). The national/local legislation barely meets the international standard on even half of the 46 evaluation criteria. There is an absence of minimal labour rights under the legislation. Workers are deprived of access to decent work in nearly every aspect of working life.

2 - Basic Access to Decent Work

Minimal labour rights are provided under the legislation in countries with a rating of 2 (Basic Access to Decent Work). There are systematic violations of workplace rights through statutory means. Workers have nominal access to decent work in a few aspects of working life only. The national/local legislation does not meet the international standard on nearly 20 of the 46 evaluation criteria.

3 - Limited Access to Decent Work